Table of Contents

Historical Context

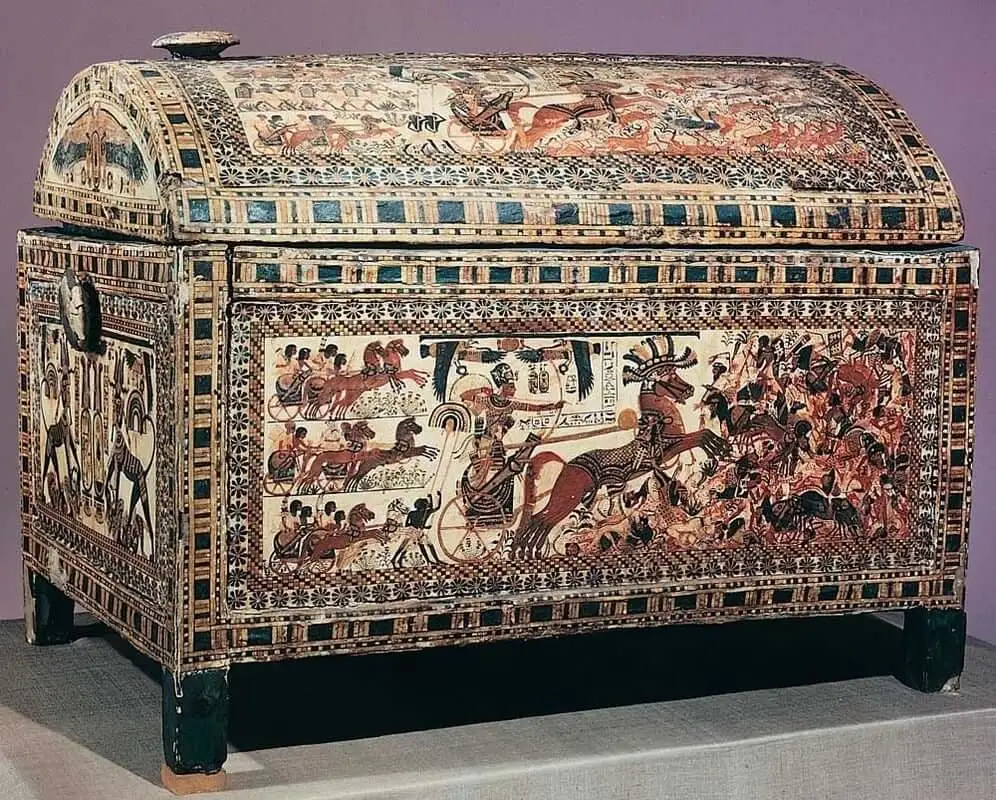

The battle scene on the papyrus is characteristic of New Kingdom Egyptian art (c. 16th–11th century BC), when pharaohs frequently celebrated military victories in their artwork (Relief Representation of a Battle Scene · Brooklyn Museum). The presence of a horse-drawn chariot and composite bow firmly places the scene in this era, since chariots were introduced to Egypt only at the start of the New Kingdom (Chest of Tutankhamun with Miniature Panoramas - Egypt Museum). Based on the artistic style and iconography, the scene likely dates to the 18th Dynasty. In fact, it closely matches a famous depiction from the reign of Tutankhamun (1332–1323 BC) (Egyptians in battle against the Nubians - Egypt Museum). The papyrus image appears to be modeled after a battle scene associated with Tutankhamun – possibly a reproduction of the painting on a wooden chest found in his tomb ( "Tutankhamun Papyrus" ). That chest’s artwork portrays the young pharaoh triumphing over foreign enemies in classic New Kingdom fashion. If so, the pharaoh in the scene would indeed be Tutankhamun, shown as a victorious warrior-king despite his short reign. More broadly, the scene follows a template used by many New Kingdom rulers (from Thutmose III to Ramesses II) to illustrate their military prowess, divine right to rule, and the subjugation of Egypt’s enemies.

Depiction of the Battle

In the image, the Egyptian pharaoh charges into battle riding a horse-drawn chariot, with reins likely tied around his waist for control while both hands wield a bow and arrow. He is depicted at a larger scale than other figures – a deliberate artistic convention to signify his importance (Relief Representation of a Battle Scene · Brooklyn Museum). The king is shown in the act of shooting arrows into a chaotic crowd of enemies. His horses gallop forward, and enemy warriors are trampled under the chariot wheels or hooves. Several fallen foes lie sprawled on the ground, and others appear to cower or flee in disarray before the pharaoh’s onslaught ( "Tutankhamun Papyrus" ). The enemies can be identified as foreigners by their distinct attire and features. (For example, if the scene is based on Tutankhamun’s chest, one side showed Nubian enemies with darker skin and African attire, while the other depicted Asiatic enemies with fairer skin, beards, and different dress (Egyptians in battle against the Nubians - Egypt Museum) (Egyptians in battle against the Nubians - Egypt Museum).) In the papyrus painting, some enemy figures seem to be woman and children among the vanquished, indicating that the entire populace of the enemy is subdued (not just the warriors). The Egyptian king’s own forces are only hinted at – in some versions of this scene, behind the pharaoh there are rows of archers and infantry in orderly formation (Egyptians in battle against the Nubians - Egypt Museum). However, the focal point is the pharaoh himself: he dominates the composition, alone in front, emphasizing that the victory is primarily his personal achievement. Notably, the scene includes dogs attacking the enemies: one or more hounds leap at the fallen or fleeing foes under the horses ( "Tutankhamun Papyrus" ). This detail of royal hunting dogs joining the fray adds to the drama of the battle depiction. Overall, the artwork presents a vivid snapshot of battle – the monarch as an unstoppable force scattering a panicked enemy, from chariot-back, with bow drawn and arrows flying.

Symbolism of Key Elements

Ancient Egyptian battle scenes were never mere literal battle snapshots; each element carries symbolic weight, reinforcing the message of pharaoh’s might and divine favor:

- Dogs: The inclusion of dogs attacking the enemies is symbolic of pharaoh’s ferocity and the thoroughness of his victory. Egyptians did use hunting dogs and sometimes war dogs, and pharaohs are often shown with loyal hounds running alongside their chariot (The Role and Significance of Dogs in Ancient Egypt) (The Role and Significance of Dogs in Ancient Egypt). In this scene the dogs represent the king’s power extending even to nature – the royal hounds are literally let loose on the foes, as if the enemies are wild prey. This imagery likens the battle to a hunt, implying the foreigners are no more than game to be run down and torn apart. It also reflects the insult of calling enemies “dogs.” Letting actual dogs attack them in art visually dehumanizes the foes and demonstrates total domination. The loyalty and swiftness of the dogs further underline that all forces (human or animal) are marshalled in service of the Egyptian king’s victory (The Role and Significance of Dogs in Ancient Egypt). In essence, the dogs enhance the ferocity and completeness of pharaoh’s triumph.

- Women (and Children): The presence of women (and sometimes children) among the vanquished enemies conveys the totality of the pharaoh’s conquest. Egyptian artists sometimes showed foreign women and children in scenes of war or its aftermath – typically as part of captive processions or chaotic flight from a besieged city (Relief of a Captive Foreign Woman and Child and a Nubian Mercenary | Middle Kingdom | The Metropolitan Museum of Art). Including women emphasizes that the enemy’s entire society has been defeated, not just its army. It also serves to highlight the king’s role as protector of Egypt: by defeating the foreign men, he subjugates their women and children, preventing them from ever threatening his people. In one ancient example, a relief from Pharaoh Mentuhotep II’s temple (Middle Kingdom) depicted a victorious siege where “defeated foreigners, including women and children, were then led into captivity,” symbolizing the king’s complete subjugation of the enemy (Relief of a Captive Foreign Woman and Child and a Nubian Mercenary | Middle Kingdom | The Metropolitan Museum of Art). Such imagery wasn’t about glorifying violence against civilians per se, but about illustrating the utter defeat and humiliation of Egypt’s foes – their warriors slain and their survivors at the mercy of the pharaoh. It also subtly indicates the mercy or control of the king: he has the power to either spare or enslave these vulnerable captives. Thus, the women in the scene accentuate pharaoh’s domination and the idea that opposing Egypt leads one’s entire lineage to ruin.

- Fallen Enemies on the Ground: The ground in front of the pharaoh’s chariot is littered with collapsed enemy soldiers. These fallen figures, often drawn in contorted postures, with weapons dropped and sometimes arrows piercing their bodies, are a direct symbol of the king’s military prowess. Piles of enemy dead (or wounded) were a common feature in Egyptian battle compositions (Relief Representation of a Battle Scene · Brooklyn Museum). They visually communicate that any who oppose the pharaoh will be destroyed and trampled underfoot (Relief Representation of a Battle Scene · Brooklyn Museum). Often, Egyptian art would exaggerate this element – showing heaps of bodies to signify an overwhelming victory (in reality, numbers might be inflated, but in art it’s the impression that counts). The pharaoh’s chariot riding over the enemies is an especially powerful image: it signifies that the king literally crushes those who rebel against him. In inscriptions, pharaohs boasted of making their enemies “a pile of corpses” ( The Digital Library Of Inscriptions and Calligraphies - Painted wooden chest of Tutankhamun ), exactly what is illustrated here. The chaotic sprawl of the fallen also has a deeper ideological meaning: in Egyptian ideology, foreign enemies were equated with forces of chaos. Portraying them as a disordered heap on the ground (sometimes tangled with each other and their broken chariots) reinforces that idea (Relief Representation of a Battle Scene · Brooklyn Museum) (Relief Representation of a Battle Scene · Brooklyn Museum). By contrast, the pharaoh and his army are the bringers of Ma’at (cosmic order), often shown in clean, organized lines. Thus, the fallen figures symbolize both the physical defeat of Egypt’s foes and the triumph of order over chaos. Their fate serves as a propagandistic warning: this is what becomes of enemies of Egypt.

Hieroglyphic Inscriptions

Ancient Egyptian artists typically accompanied such battle scenes with hieroglyphic texts that identify the pharaoh and glorify his victory. In the provided image, one can likely see hieroglyphic captions near the pharaoh or around the scene. These would include the king’s cartouche name and titles, as well as short epithets and phrases describing the conquest. For example, in Tutankhamun’s battle scene, an inscription on the chest’s panel explicitly praises him as “the good god, the son of Amon, the valiant one, without his equal, a possessor of strength who tramples hundreds of thousands, making them into a pile of corpses.” ( The Digital Library Of Inscriptions and Calligraphies - Painted wooden chest of Tutankhamun ). This kind of text, if present, would be written in the columns of hieroglyphs nearby, effectively narrating the image. The pharaoh’s throne name (for Tutankhamun it was Nebkheperure) or personal name would be enclosed in an oval cartouche, making it clear who the triumphant king is. Additionally, hieroglyphs might label the vanquished people or lands – for instance, terms like “vile Nubians” or “Asiatics” could appear, or the names of specific enemy chiefs and foreign regions, as was common in temple battle reliefs. These labels and boastful descriptions were integral to the scene’s message: they left no doubt about the identity of the king and the scope of his victory. The reference to the pharaoh as “Son of Amon” (son of the god Amun) is especially significant ( The Digital Library Of Inscriptions and Calligraphies - Painted wooden chest of Tutankhamun ). It asserts divine parentage, implying that the king has the gods’ direct support. In essence, the hieroglyphic text functions to amplify the imagery – it turns the visual propaganda into written praise, recording that the pharaoh (with help from the gods) has crushed his enemies utterly. If any specific hieroglyphs are visible in the image, they likely convey these royal titles and victory chants, anchoring the scene in its proper historical and religious context.

Artistic Style and Influence

The style of the painting aligns strongly with New Kingdom artistic conventions for battle scenes. The composition is dynamic and not bound by registers (horizontal ground lines). Earlier Egyptian art often organized scenes in neat rows, but by the New Kingdom, battle scenes became energetic sprawl across the surface, especially to depict the chaos of the enemy. In this papyrus, the chaotic pile of defeated foes and the forward rush of the chariot are reminiscent of New Kingdom temple reliefs that show battles as a single dramatic tableau ( The Digital Library Of Inscriptions and Calligraphies - Painted wooden chest of Tutankhamun ). The pharaoh is the central, largest figure – a hierarchical scaling that immediately conveys his importance relative to both friend and foe (Relief Representation of a Battle Scene · Brooklyn Museum). His posture (standing firm in the chariot with weapon drawn) and the rearing horses create a sense of motion and heroism. We see a keen attention to detail in the tiny figures of the enemies, the horses’ harness, and the weaponry, which is characteristic of the meticulous art from Tutankhamun’s tomb objects (Chest of Tutankhamun with Miniature Panoramas - Egypt Museum) (Chest of Tutankhamun with Miniature Panoramas - Egypt Museum). The colors (if the image is in color) likely are applied in flat patches bounded by line work – typical of Egyptian painting on papyrus or wood – with bold contrasts to distinguish the king (often shown with the blue war crown or the nemes headdress) from the less vividly depicted enemies.

This scene’s style is notably similar to the battle panoramas on temple walls crafted in subsequent dynasties. It’s documented that Tutankhamun’s chest scenes, with their lively and jumbled enemy masses, may have inspired artists of the 19th Dynasty (like Seti I and Ramesses II) in how they composed later battle reliefs ( The Digital Library Of Inscriptions and Calligraphies - Painted wooden chest of Tutankhamun ). For instance, Pharaoh Ramesses II (1279–1213 BC) famously depicted the Battle of Kadesh on his temple walls in a comparable fashion: he is shown charging in his chariot, twice life-size, drawing a bow, while Hittite chariots crash and soldiers tumble all around under his horses (Battle of Kadesh - Egypt Museum). In one relief at Abu Simbel, Ramesses II is portrayed “slaying one enemy while trampling another” under his chariot, almost exactly the same motif as our papyrus scene (Battle of Kadesh - Wikipedia). Ramesses II even included his pet lion in some depictions (the lion running beside the chariot as an analog to the dogs in Tutankhamun’s scene) to emphasize his ferocity and favor from the gods. Earlier in the New Kingdom, Thutmose III (1479–1425 BC) had battle scenes carved at Karnak after the Battle of Megiddo. Those show the pharaoh in the classic smiting pose (grasping a group of captive enemies by the hair and ready to smash them with a mace) and also marching troops—more rigid than later art, but still conveying the same message of total victory (Battle of Megiddo (15th century BC) - Wikipedia) (Battle of Megiddo: Pharaoh Thutmose III vs. Canaanites | TheCollector). By Tutankhamun’s time, artists combined the ferocity of the smiting motif with the dynamic chariot imagery that became possible with the introduction of horses and chariots. Thus, the papyrus scene falls squarely in the New Kingdom tradition: it shares elements with earlier examples like Thutmose III’s iconography of domination, and directly prefigures the grand battle scenes of later pharaohs like Seti I and Ramesses II. In terms of artistic influence, scenes like this reinforced a standard formula for depicting warfare that persisted throughout the New Kingdom – a formula driven more by symbolic messaging than by realism, but one that powerfully conveyed the might, bravery, and supremacy of the pharaoh on the battlefield.

Cultural and Mythological Significance

Ancient Egyptian battle scenes such as this were as much ideological statements as they were historical records. Culturally, the pharaoh was regarded not just as a political leader but as a semi-divine guardian of Egypt, responsible for maintaining Ma’at – the cosmic order and justice. Foreign enemies were often associated with Isfet, or chaos. Therefore, the imagery of the king defeating foreign armies carried a deep mythological subtext: it symbolized the forces of order (Egypt, led by the god-supported pharaoh) triumphing over the forces of chaos (the foreign threats) (Relief Representation of a Battle Scene · Brooklyn Museum). The scene can be read as a visual metaphor for the triumph of civilization over barbarism, and of gods’ chosen ruler over the unruly outsiders. In many temple reliefs, this concept is made explicit by accompanying texts or even depictions of gods—for example, a god like Amun or Montu (the war god) might be shown blessing the king or handing him a weapon, indicating that the pharaoh fights with divine sanction. In our papyrus, while no gods are overtly pictured, the pharaoh’s colossal presence and the hieroglyphic epithet “Son of Amon” ( The Digital Library Of Inscriptions and Calligraphies - Painted wooden chest of Tutankhamun )imply that Amun’s power flows through him. The king’s unequaled strength is thus a gift from the gods, and the victory is portrayed as ordained by divine will.

This propagandistic element served political purposes. Such images broadcast a clear message to both Egyptians and foreign onlookers: Egypt’s king is invincible by virtue of divine favor. The Brooklyn Museum notes that these scenes could even function as warnings to potential enemies of Egypt – showing them the “inevitable destruction” that would befall them if they opposed the pharaoh (Relief Representation of a Battle Scene · Brooklyn Museum). At the same time, for the Egyptian populace, it reinforced faith in their leader’s ability to protect them and uphold cosmic order. The incorporation of semi-mythical elements – for instance, pharaohs depicted as a sphinx tramping enemies (as Tutankhamun is on other panels of the chest) (Chest of Tutankhamun with Miniature Panoramas - Egypt Museum), or the larger-than-life scale of the king – blurs the line between human king and deity. In art, the pharaoh could be shown performing feats akin to the gods’ victories over demons. This ties into the wider Egyptian mythos: one might liken the pharaoh’s vanquishing of armies to Horus defeating the forces of Set (chaos), or Ra overcoming the serpent Apophis each night. Every enemy killed by the king is an embodiment of chaos that has been subdued. Even the dogs in the scene have a mythological resonance – dogs (or jackals) bring to mind Wepwawet, a war-like deity whose name means “Opener of the Ways,” often represented as a canid guiding the pharaoh to victory. Whether intended or not, the dogs supplement the sense that even nature’s predators side with Egypt’s divine ruler.

In summary, the battle papyrus is not just a historical recounting – it is a crafted narrative of power. It uses visual symbolism to elevate the pharaoh’s status to near-divine, emphasize that his victories are both inevitable and cosmically significant, and legitimize his rule by showing him as the protector of his people and the tamer of chaos. When compared to other known battle scenes in Egyptian art – from Thutmose III’s reliefs to Ramesses II’s Kadesh carvings – this image carries all the hallmarks of Egyptian royal propaganda. It leverages art to convey political mythology: that the pharaoh, backed by the gods, will triumph over all enemies foreign and domestic, ensuring Egypt’s stability and the eternal continuation of Ma’at. Such is the enduring significance of this papyrus battle scene, which encapsulates both the historical ethos of New Kingdom Egypt and the timeless mythological narrative of good’s victory over evil.