Table of Contents

Introduction

The Voice of the Silence is a renowned mystical text by Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, co-founder of the Theosophical Society. First published in 1889, it is considered “a spiritual classic of incomparable beauty and power” within Blavatsky’s body of work. Unlike her extensive doctrinal tomes Isis Unveiled and The Secret Doctrine, which expound occult philosophy, The Voice of the Silence is a slender volume of practical wisdom and poetic instruction. Blavatsky intended it as a handbook for earnest disciples (referred to as Lanoos) on the spiritual path . Composed in an aphoristic, verse-like style, the text distills the core of esoteric ethics and mysticism, guiding the seeker toward inner enlightenment and compassionate service. Its significance lies in both its inspirational beauty and its role in elucidating key Theosophical ideals, such as the unity of all life and the supremacy of selfless love, in a concise, contemplative format.

Blavatsky claimed that The Voice of the Silence was not her original invention but a translation of selections from an esoteric source known as The Book of the Golden Precepts. According to her, this secret work consists of ancient spiritual maxims she had learned during her travels in the East . These precepts form part of the training given to mystic students in certain Himalayan esoteric schools, where knowledge of them “is obligatory” . Blavatsky stated that she had memorized many of these teachings and thus could render them into English with relative ease. She presents The Voice of the Silence as “chosen fragments” meant “for the daily use of Lanoos (disciples)” – implying it is a practical manual of daily spiritual discipline. The fragments she translated are drawn from the same archaic lineage as the stanzas of the Book of Dzyan (the mysterious text underlying The Secret Doctrine) and a work called Paramârtha伝 . In Theosophical lore, these texts share a common origin in the once-unwritten “Wisdom-Religion” of antiquity. Blavatsky suggests that the Book of the Golden Precepts and its teachings stem from a primeval source, portions of which also surface in Hindu and Buddhist scriptures. Indeed, she notes that its “maxims and ideas” can be found in works like the Jñâneśvari (a commentary on the Bhagavad Gita) and in certain Upanishads, reflecting the overlap between this esoteric doctrine and known Eastern philosophies . This origin story situates The Voice of the Silence within the Theosophical context as a genuine expression of the Perennial Wisdom — the idea that all religious traditions spring from one universal truth.

Within Theosophy, The Voice of the Silence occupies a special place as an inspired text of practical mysticism. It is not a theoretical treatise but a guide to inner life, richly symbolic and meant to be meditated upon. Blavatsky herself, writing under the initials “H. P. B.”, dedicated the book “to the Few” who are resolute in treading the occult path . In the late 19th-century milieu, the work served to reinforce Theosophy’s core ethical principle: the pursuit of spiritual enlightenment must be wed to compassion for all beings. As a bridge between Eastern mystical teachings and Western esoteric readership, The Voice of the Silence encapsulates the Theosophical approach — blending Buddhist and Vedantic concepts with Western occult understanding. It emphasizes inner spiritual development (often called the “Heart Doctrine” in Theosophy) over mere intellectualism or dry dogma (“Eye Doctrine”) . In summary, the text’s significance lies in its role as a succinct, practical embodiment of Blavatsky’s esoteric teachings, providing aspirants a poetic roadmap to self-transcendence and altruistic service.

The Structure and Content

Blavatsky’s Voice of the Silence is divided into three parts, often referred to as Fragments, each of which presents a different facet of the spiritual journey. These three fragments are titled: The Voice of the Silence, The Two Paths, and The Seven Portals . Together, they form a progressive narrative of awakening: from initial discipline and inner attunement, to the ethical choice between two spiritual ideals, and finally to the trials one must undergo to attain enlightenment. Blavatsky’s role here is as a translator and annotator of these arcane teachings — she provides occasional footnotes and explanations, but largely lets the mystical verses speak for themselves. In her preface, she mentions trying her best to preserve the “poetical beauty of language and imagery” of the original . As such, the content is presented in a semi-aphoristic, poetic prose that invites contemplation. Each fragment can be seen as a step in a cohesive spiritual instruction, yet each has its own emphasis and symbolic framework.

Fragment I: “The Voice of the Silence.”

The first fragment, sharing the book’s title, lays the foundation for the entire work. It opens with a series of succinct maxims addressing the disciple directly. The theme here is the preparation of the mind and soul to perceive the inner spiritual voice – the Voice of the Silence. The text warns of the “dangers of the lower Iddhi (psychic powers)” and immediately directs the aspirant’s attention to the realm of higher perception. The famous opening lines counsel the disciple on the necessity of mastering one’s thoughts and senses: “He who would hear the voice of Nâda, ‘the Soundless Sound,’ and comprehend it, he has to learn the nature of Dhâranâ” . In other words, one must achieve profound concentration (Dhāraṇā) and interior focus to detect the mystical inner sound (Nâda) that emanates from the Silence of the spiritual self. The fragment goes on to describe the illusory nature of the lower mind and sense-world – “The Mind is the great Slayer of the Real. Let the Disciple slay the Slayer” . This striking aphorism encapsulates a key teaching: our ordinary mind, tangled in perceptions and desires, “slays” or obscures the Real (Ultimate Reality). The disciple is urged to still the mind’s distractions and overcome the illusion of separateness.

Fragment I uses vivid allegories to illustrate the path of inner purification. For example, it speaks of three symbolic “Halls” – the Hall of Ignorance, the Hall of Learning, and the Hall of Wisdom – through which the pilgrim soul must pass . These represent stages of consciousness: the ordinary worldly state (ignorance), the phase of study and probation (learning, where truth is glimpsed but still mixed with temptation – “under every flower a serpent coiled” ), and finally the state of true insight (wisdom) which opens into the “shoreless waters” of Akshara, the indestructible source of omniscience . To progress, the disciple must conquer various illusions of the self. The text often addresses the aspirant’s soul directly, using evocative imagery – for instance, the soul that too readily feels delight or despair at life’s experiences is likened to a “shy turtle” that withdraws into the shell of selfhood . The instruction is to remain steadfast and focused on the eternal reality (Sat), forsaking the clamor of the transient world (Asat) . Only when one “has ceased to hear the many” distractions can one discern “the ONE – the inner sound which kills the outer” . In essence, Fragment I guides the disciple in silent contemplation and discrimination between the Real and the unreal, so that the true Voice of the Silence – the voice of the higher Self or divine wisdom – can be heard within. Blavatsky’s footnotes in this section identify this “Silent Speaker” or “Great Master” as the Higher Self, equating it with the Buddhist Avalokiteśvara or the Ātman of the Hindus . Thus, the first fragment’s content centers on personal spiritual discipline, inner awakening, and the attunement to the divine essence within one’s heart.

Fragment II: “The Two Paths.”

The second fragment shifts focus to a moral and philosophical choice that faces the advanced disciple upon attaining some degree of enlightenment. This section is significantly shorter, but its message is pivotal: it contrasts the two possible paths of spiritual attainment. On one hand is the path of personal liberation – attaining Nirvāṇa for oneself, typified by the figure of the Pratyeka-Buddha (the “self-enlightened Buddha”). On the other hand is the path of compassion – renouncing immediate liberation and returning to the world to aid others, typified by the Bodhisattva, the future Buddha who sacrifices his bliss for the sake of all beings. Blavatsky’s text makes it clear that the higher ideal is the Bodhisattva path, sometimes called the “Path of Woe” because it involves voluntarily taking on the suffering of continued existence to help humanity . The fragment dramatizes the moment of choice in lofty, heart-stirring verses. We are told that when the disciple stands at the threshold of Nirvāṇa, having “won the battle” and earned the right to eternal peace, a voice of divine compassion prompts a profound question: “Can there be bliss when all that lives must suffer? Shalt thou be saved and hear the whole world cry?” . In this poetic way, the text poses the Bodhisattva’s dilemma – to accept personal salvation or to postpone it until all others can be saved.

Blavatsky’s interpretation leaves no doubt as to the noble choice: the fragment praises the one who elects to remain and serve. “He who becomes Pratyeka-Buddha makes his obeisance but to his Self. The Bodhisattva... says in his divine compassion: ‘For others’ sake this great reward I yield’ — accomplishes the greater Renunciation.” . The Pratyeka-Buddha, in seeking enlightenment for himself alone, is implicitly labeled as following the lesser, “selfish” route. By contrast, the Bodhisattva’s self-abnegation is extolled as the supreme heroism – “a Saviour of the World is he” . Fragment II thus defines the two paths as the Eye Doctrine vs. Heart Doctrine, or the path of “Rest and Liberation for the sake of Self” versus the path of “long and bitter duty” and renunciation for the sake of others . Blavatsky underscores that the disciple’s time will come to choose, and the true adept will choose the harder path of compassion. In Theosophical context, this reflects the ideal of the Nirmāṇakāya – the enlightened being who renounces Nirvāṇa to remain in touch with the world’s suffering and guide humanity. The content of Fragment II, though brief, is thus a profound ethical teaching wrapped in metaphor: it cements the primacy of universal love and sacrifice in genuine spiritual work. Blavatsky’s own footnotes align this doctrine with esoteric Buddhism, calling the compassionate path the “Heart Doctrine” (esoteric teaching that comes straight from Gautama’s heart) as opposed to the “Eye Doctrine” (exoteric or intellectual approach) . In summary, The Two Paths fragment urges the disciple to adopt the Bodhisattva ideal – to become, in effect, a co-worker with the divine in the redemption of all beings, rather than seeking a private escape from the world.

Fragment III: “The Seven Portals.”

The final and longest fragment details the arduous ascent the Bodhisattva-disciple must undertake through seven metaphoric gateways of virtue and spiritual power. Having committed to the compassionate path, the aspirant now must qualify himself to become a true savior of mankind. This section is structured as a dialogue between the disciple (Śrāvaka, “listener”) and the teacher (Upādhyāya), and it has the character of an initiation ritual or catechism. The teacher asks which path the disciple will choose: the steep but shorter path of the Four-fold Dhyāna (meditative absorptions, corresponding to the Eye Doctrine and solitary liberation), or the still harder path of Pāramitās, the perfections of virtue (the Heart Doctrine leading to Buddhahood) . The disciple declares his choice for the “greater Yana” (the greater vehicle of salvation for all) . What follows is an enumeration and explanation of the seven portals which correspond to seven keys or virtues that must be mastered. These seven portals symbolize successive initiatory thresholds on the spiritual journey – at each portal, the disciple must conquer certain “cruel crafty Powers — passions incarnate” that guard the gate. In other words, one’s inner demons or weaknesses must be overcome step by step as one cultivates the highest virtues.

Each of the seven portals is linked to a specific transcendental virtue, identified with the Sanskrit term Pāramitā (perfection). Blavatsky’s text lists them poetically as golden keys that open the gates:

- Dāna – the key of charity and love immortal, i.e. generosity of spirit .

- Śīla – the key of harmony in word and act, i.e. pure ethical conduct that creates balance and negates future karma .

- Kṣānti – the key of sweet patience that nothing can ruffle, i.e. forbearance in all trials .

- Virāga – the key of indifference to pleasure and pain, i.e. dispassion and conquest of illusion .

- Vīrya – the key of dauntless energy that fights its way to supernal truth, i.e. vigor or fortitude in pursuit of the good .

- Dhyāna – the key of profound meditation, whose golden gate once opened leads the adept toward the realm of Sat (Being, Truth) eternal .

- Prajñā – the key of wisdom, the final consummation that “makes of a man a god, creating him a Bodhisattva, son of the Dhyānis” .

These seven keys correspond to the well-known six perfections of Mahāyāna Buddhism (generosity, morality, patience, energy, meditation, wisdom), with an added emphasis on Virāga or detachment, making seven in total. The text itself remarks that there are “virtues transcendental, six and ten in number” – an allusion to different listings of Pāramitās (some traditions enumerate six, others expand to ten). Blavatsky’s choice to enumerate seven corresponds to the Theosophical fondness for the septenary; it also aligns with seeing Prajñā (wisdom) as the crowning seventh portal that synthesizes the rest.

In Fragment III’s dramatic allegory, the disciple must pass through each portal by fully developing the respective virtue and defeating its opposing passion. For instance, to pass the Portal of Dāna, one must utterly uproot selfishness and embody charity; to pass Śīla, one must live in complete harmony with truth; to pass Kṣānti, one conquers anger and irritation, and so forth. Each conquered portal brings the seeker closer to the ultimate enlightenment of a Bodhisattva. The text describes this journey as crossing the waters to “the other shore” of liberation , a common Buddhist metaphor (Pāramitā literally means “that which carries across”). The culmination is the seventh portal of Prajñā, divine wisdom, whose attainment literally deifies the disciple – “creating him a Bodhisattva, son of the Dhyânis” (the Dhyāni-Buddhas or celestial enlightened beings) . The successful initiate becomes an Arhan, an enlightened being, but one who has taken the Bodhisattva vow to use that enlightenment for the world.

Blavatsky’s interpretation throughout this fragment (conveyed in her annotations and the overall framing) connects these trials to spiritual initiation. The “Seven Portals” can be seen as seven degrees of initiatory attainment, each demanding not only moral excellence but inner conquest of illusion. She notes that once the disciple has entered the stream (Srotāpatti, the first stage of sanctification in Buddhism) he has but a fixed number of rebirths left before final liberation – indicating that passing even the first portal marks one’s irreversibly assured progress toward enlightenment. The tone of this fragment is one of stern but compassionate encouragement. The Master urges the disciple onward, “bear in mind the golden rule”, and promises that once these portals are mastered, the reward is the true knowledge of the Secret Heart. In the finale of the text, when the disciple is about to attain the final goal, even Nature herself rejoices: “From the four-fold manifested Powers a chant of love ariseth… ALL NATURE’s wordless voice in thousand tones ariseth to proclaim: … A Pilgrim hath returned back from the other shore… Peace to all beings.” . Thus, Fragment III’s content richly symbolizes the rite of passage into enlightened consciousness — an achievement that ultimately benefits the whole world. Blavatsky’s presentation here is her interpretation of age-old esoteric teachings: that enlightenment is not a sudden grace but the result of conquering self through disciplined virtue, and that the highest adeptship is attained in order to better uplift humanity.

Philosophical and Esoteric Analysis

Nada, the “Soundless Sound.”

One of the most intriguing mystical concepts in The Voice of the Silence is Nâda, described as the “Soundless Voice” or the “Voice of the Silence” itself . Philosophically, Nâda represents the inner divine resonance – a mystic sound that is not heard by the physical ear but by the soul. Blavatsky’s text teaches that the disciple, in deep meditation, may hear this inner sound once all outer noises and distractions are silenced. “When he has ceased to hear the many, he may discern the ONE – the inner sound which kills the outer.” . This ONE sound is Nada, the sacred tone of the universe, often likened to AUM (Om) in Indian tradition. In fact, Blavatsky’s footnote equates Nâda with a Senzar (occult) term and suggests the phrase could be rendered “Voice in the Spiritual Sound” – implying that Nada is the subtle voice arising within the vibratory field of universal consciousness. Esoterically, hearing the “Voice of the Silence” is a metaphor for contacting one’s own Higher Self or inner Master. It is soundless in the sense that it is an unstruck sound (anāhata nāda in yogic terms) – a vibration not produced by any two things striking together, but inherent in śūnyatā or the void. This concept has parallels in many mystical schools: for instance, Hindu Yoga speaks of the Anahata sound heard in the heart chakra, and some Buddhist texts refer to the “voice of the Dharmakaya” heard in meditative absorption. Blavatsky’s inclusion of this idea points to the profoundly experiential nature of the path – beyond dogma, the seeker must literally refine his consciousness to perceive the inner divine guidance. Philosophically, Nada signifies the omnipresent Logos or Word that vibrates through creation; to hear it is to become aligned with the heartbeat of the cosmos. Thus, Nada in The Voice of the Silence symbolizes the highest intuition or direct inner experience of truth. Its mystical significance is that it marks the soul’s entry into deeper states of awareness: as the text indicates, only when the pupil attains inner Dhāraṇā (concentration) and becomes indifferent to sensory input does this subtle voice emerge . In essence, Nada is the Voice of the Silence—the paradoxical “sound” of absolute quietude—through which the universe and one’s own higher nature speak to the enlightened mind.

The Path of the Bodhisattva vs. the Pratyeka-Buddha.

A central philosophical theme in The Voice of the Silence is the sharp contrast between two archetypal spiritual paths. Blavatsky highlights this as the choice between the Bodhisattva ideal and the Pratyeka-Buddha ideal. In Buddhist terms, a Pratyeka-Buddha is a solitary sage who achieves Nirvana alone and does not teach others, while a Bodhisattva forgoes the final Nirvana until all beings can be saved, out of infinite compassion. The text frames this as a moral and spiritual crossroads for the adept. On one side stands what might be called the path of self-liberation – profound, but ultimately centered on one’s own escape from the world of suffering. On the other side stands the path of self-sacrifice – longer and more arduous, as it entails “woe” and continued reincarnations, yet dedicated to the liberation of all. Blavatsky’s work unambiguously extols the Bodhisattva path. She describes the temptation of bliss that confronts the successful yogi and counters it with the poignant call of compassion: “Sweet are the fruits of rest and liberation for the sake of Self; but sweeter still the fruits of long and bitter duty… Renunciation for the sake of others, of suffering fellow men.” . The philosophy here is that true enlightenment cannot be selfish. Any attainment of wisdom is seen as hollow unless the adept uses it to alleviate the pain of others. This reflects the Mahayana Buddhist ethos and also resonates with Theosophical ethics which prize universal brotherhood above all.

In esoteric terms, the Pratyeka path is sometimes associated with what Theosophy would call the left-hand path or spiritual selfishness (even if it involves rigorous discipline, it lacks the element of compassion). The Bodhisattva path, conversely, is the epitome of the right-hand path – the way of the White Magician or saint who lives for the world. Blavatsky uses strong language: the Pratyeka-Buddha “makes his obeisance but to his Self,” implying a kind of spiritual egoism, whereas the Bodhisattva yields even the reward of Nirvana for others’ sake . Philosophically, this dichotomy highlights a major theme of the text: the unity of Self with all selves. If one truly perceives the oneness of all beings (a fundamental truth in both Vedanta and Mahayana Buddhism), then seeking personal salvation to the exclusion of others is seen as an illusion – because in the highest sense, there is no isolated personal self to save. The Bodhisattva realizes that Nirvana and Samsara (the world of suffering) are not two different places to flee between; rather, Nirvana is a state of liberation that can be lived in the world as compassionate action. This is why the Bodhisattva “remains unselfish till the endless end” , effectively choosing to work in the world of Samsara out of enlightened mercy. Blavatsky’s emphasis on this choice serves to align The Voice of the Silence with the loftiest mystical traditions: it echoes the Christ-like sacrifice (more on that parallel later) and the ideal of the spiritual warrior whose victory is not escaping life, but transforming it. In summary, the text’s philosophical stance is that compassion is the highest law. Enlightenment devoid of compassion is incomplete. Therefore, the seeker is urged to become a Bodhisattva, embodying the enlightenment that hears the world’s cry and responds, rather than a Pratyeka-Buddha who turns away into isolated peace. This teaching bridges metaphysics and ethics, showing that one’s conception of self (whether separate or universal) determines one’s spiritual destiny.

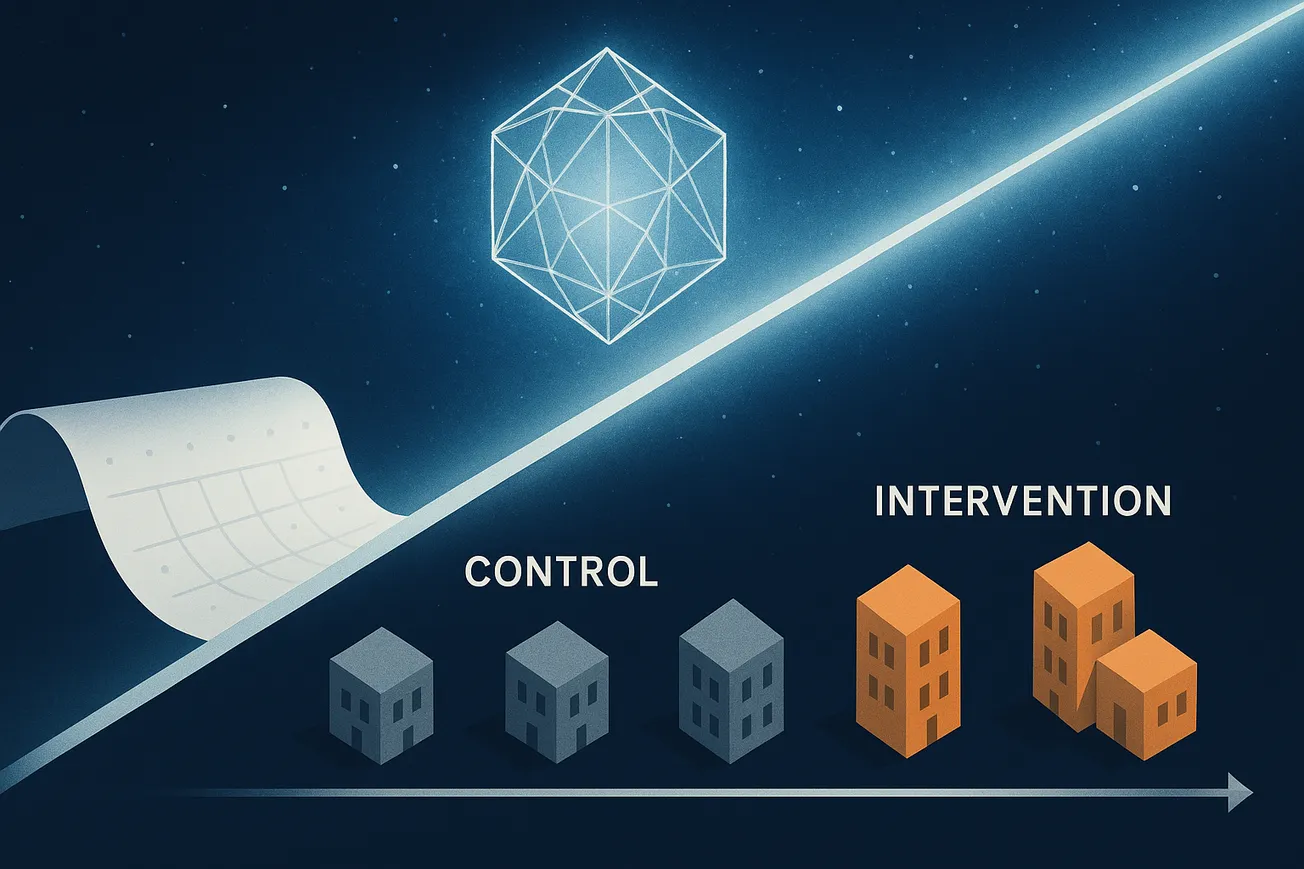

The Seven Portals as Symbols of Initiation.

The imagery of the Seven Portals in Fragment III provides a rich symbolic map of the soul’s journey and has deep esoteric meaning. Each portal can be seen as both an inner state and an initiatory ordeal. In many esoteric traditions (Eastern and Western alike), progress on the spiritual path is marked by a series of tests or gateways that the aspirant must pass through. Blavatsky’s seven portals correspond to mastering the seven pāramitās (perfections of virtue), which suggests that the true initiations are conquests over one’s lower nature. Symbolically, a portal is something that both blocks the way and offers passage – it represents a critical threshold where one either fails (turns back, falls to a temptation) or succeeds and moves to the next level. The golden keys to open these gates are the virtues themselves . This conveys that no external agency grants admission; only the flowering of the appropriate quality in the disciple’s own heart will unlock the gate. In practical terms, for example, the “Portal of Dana (Charity)” will only open when true unselfish charity fills the disciple – any residual selfishness will act as a lock barring the way. In this manner, the seven portals are the stages of self-transformation. They also align with the idea of the septenary constitution of both the human and the cosmos, a common idea in Theosophy (seven principles of man, seven planes of being, etc.). Thus, passing through all seven portals implies full realization on every level of one’s being.

Initiatically, we can parallel the seven portals with other systems: In Vedantic and Yogic terms, they might be likened to raising Kundalini through seven chakras, each chakra requiring purification of certain qualities; in Western esoteric orders, one might think of the seven degrees of initiation or the ascent through the seven classical planets, each with its trials. The Voice of the Silence explicitly casts the portals as guarded by “cruel crafty Powers — passions incarnate”. This evokes the archetype of the hero’s journey, where dragons or demons guard the treasure at each stage. Here the “demons” are inner: greed, lust, anger, pride, etc., corresponding inversely to the virtues to be attained. For instance, at the portal of Kṣānti (patience), the “demon” might be anger or despair; at the portal of Śīla (harmony/morality), the demon might be temptation or moral apathy. The disciple’s fight through each stronghold is thus an allegory for deep psychospiritual work, conquering each vice and replacing it with its opposing virtue. Only by such victories can one claim the title of Arhat (adept).

The seven keys culminating in Prajñā (wisdom) also have a unifying significance. Wisdom is placed as the final synthesis – it is not just one more virtue, but the illumination that comes when all the other qualities have been perfected in balance. It “makes of a man a god” because it is the awakening of the divine nature within, the Bodhisattva state. The requirement that the disciple must “master these Pāramitās of perfection” before approaching the last gate speaks to the esoteric principle that power is given only to those who are morally fit to wield it. In occult tradition, attempting to unlock spiritual powers (siddhis) or higher states without having purified oneself is dangerous and leads to downfall. The Voice of the Silence reinforces this: the portals must be taken in order; there are no shortcuts where one can bypass ethical development to reach spiritual heights. This is initiation in the truest sense – initiation as inner transformation, not just external ceremony.

Furthermore, the number seven itself, aside from its cross-cultural sacredness, here may represent completeness. By the time the disciple stands before the seventh portal, he has integrated all aspects of his being into harmony with the divine law. Crossing the seventh portal (Prajñā) is essentially achieving enlightenment – but notably, in this text it is enlightenment wedded with compassion (since the whole training was to create a Bodhisattva). The successful initiate becomes a “new Arhan” who returns from “the other shore” with the power to bring “peace to all beings.” . The celebratory verses at the end of Fragment III imply that the initiate’s completion of the path has cosmic significance — even the forces of nature rejoice, and humanity receives a boon through the birth of a Savior. This underscores the initiatory theme: enlightenment is not an end, but the beginning of one’s true service. In summary, the Seven Portals symbolize the sevenfold path of spiritual perfection, each step being an initiation into a higher level of being. Blavatsky’s presentation weaves together Buddhist and occult motifs to portray initiation as a gradual, grueling, but glorious ascent, transforming the disciple into a Bodhisattva, an enlightened servant of the world.

Influence of Buddhist, Vedantic, and Other Mystical Traditions.

The Voice of the Silence is profoundly syncretic, reflecting Blavatsky’s view that Buddhism, Vedanta, and other ancient traditions are all streams flowing from the same Wisdom-Religion. The influence of Buddhist philosophy is perhaps most evident: the text is saturated with Sanskrit and Pāli terms common to Buddhism (Nirvana, Dharma, Skandha, etc.), and it consistently invokes Mahayana Buddhist ideals. The Bodhisattva concept, the Pāramitās, references to stages like Srotāpatti (stream-enterer) , and the general worldview of samsaric illusion and enlightenment all mark the work as one steeped in Buddhist thought. In particular, the Yogācāra (or “Contemplative Mahāyāna”) influence is notable, which Blavatsky explicitly alludes to in her preface when she mentions that the Golden Precepts are preserved where “the so-called ‘contemplative’ or Mahāyāna (Yogāchāra) schools are established” . Yogācāra Buddhism emphasizes the mind’s role in constructing reality (sometimes called the Mind-Only school) – this resonates with the text’s statements like “The Mind is the great Slayer of the Real” , implying that one’s perceived reality is a mental construct that obscures the Absolute. Moreover, the very Mahāyāna idea that compassion and wisdom must unite is the heart of the Bodhisattva doctrine in the text. We can see parallels with Buddhist scriptures: for instance, the emphasis on hearing the “inner sound” might parallel descriptions in some tantric or Zen Buddhist writings where meditators become attuned to the cosmic vibration; the description of illusions and the need to see through them echoes the Prajñāpāramitā sutras, which talk about the illusory nature of phenomena; and the refrain of aiding all sentient beings is straight out of the Bodhisattva’s vows found in texts like the Lotus Sutra. While The Voice of the Silence is not a direct copy of any single Buddhist text, it artfully blends Buddhist concepts into its fabric, effectively serving as a Mahāyāna-style guidebook for enlightenment with a distinctively Theosophical voice.

At the same time, Vedantic (Hindu) influences permeate the work. Terms like Sat (ultimate Being/Truth) and Māyā (illusion) are explicitly used . The instruction to forsake the “region of Asat (the false) to come unto the realm of Sat (the true)” could easily come from an Upanishad or from Advaita Vedanta teachings, which urge the seeker to discriminate the Real (Brahman) from the Unreal (the transient world). The concept of giving up the lower self to unite with the One Self is pure Vedanta – Blavatsky even uses the term Ātmajnānī (knower of the Self) in a footnote . The idea of Nada, the soundless sound, has counterparts in Hindu mysticism: the Nāda-Bindu Upanishad, for example, speaks of meditation on the inner sound as a means to liberation . Blavatsky directly references this Upanishad in her notes, tying the OM (AUM) vibration to the image of the Hamsa swan . The Three Halls allegory (Ignorance, Learning, Wisdom) may also reflect Vedantic stages of consciousness (e.g. the progression from gross to subtle to causal understanding). Furthermore, Blavatsky’s assertion that many of the first Buddhist arhats were Hindu Aryans suggests her view that early Buddhism and late Vedanta shared a common pool of ideas – something that is mirrored in the text’s seamless integration of Sanskrit (Hindu) and Pāli (Buddhist) terminology. The influence of the Bhagavad Gita and Jnâneshvari is also hinted at ; indeed, lines like “sweet is rest between the wings of that which is not born nor dies, but is the AUM through eternal ages” evoke the Gita’s and Upanishads’ descriptions of Brahman (the unborn, undying reality symbolized by Om). Thus, Advaita Vedanta’s monistic mysticism—emphasizing the illusory nature of personal self and the imperative to realize identity with the universal Self—undergirds much of the philosophy in The Voice of the Silence. The union of wisdom and compassion that the text preaches can also be seen as uniting Vedanta’s jnāna (wisdom of the Real) with the bhakti (devotion) ideal of selfless love for all – a synthesis common in the figure of the jīvanmukta (liberated being who lives in the world to help others).

Beyond Buddhism and Hinduism, Blavatsky’s work draws on other mystical traditions in more subtle ways. The concept of an inner “Voice of the Silence” has echoes in mystical Christianity – one is reminded of the biblical “still small voice” that speaks to the prophet, or the Logos (Word) that is heard in silence by Christian contemplatives. Blavatsky explicitly equates the Higher Self (the “Great Master” within) with Christos as understood by the ancient Gnostics . This is a profound bridge: it suggests that the Christ of the mystic is not different from the Buddha-wisdom or the Ātman; all are names for the divine Self. In this sense, the Bodhisattva ideal parallels the Christ ideal – both are embodiments of sacrificial love. A Christian mystic might phrase the Bodhisattva’s thought as “I will not enter heaven while even one soul remains in hell,” which is analogous to “Shalt thou be saved and hear the whole world cry?” . Additionally, the elevation of compassion above personal salvation strongly resonates with the teachings of Christ, who said “Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends.” In The Voice of the Silence, the Bodhisattva lays down not just physical life but even the right to Nirvana for the spiritual “friends” that are all beings. Such parallels show an underlying unity: whether one speaks of the Bodhicitta (the Bodhisattva’s compassionate resolve) or Christ-consciousness, the quality is the same.

The influence of Western esoteric traditions can also be discerned. The very format of an initiatory journey through trials evokes the Mystery schools of antiquity and the initiations of Hermetic and Rosicrucian lore. The *“chant of love” arising from the four-fold manifested Powers – Fire, Water, Earth, Air – in the finale reflects a classical element symbolism that a Western alchemist or Kabbalist would recognize. It is as if the entire natural world (the four elements) participates in the apotheosis of the initiate, which mirrors ideas in Hermeticism about the harmony between the enlightened magus and the elements. Furthermore, Blavatsky’s Theosophy often claims to revive the Perennial Philosophy (Philosophia Perennis) – the timeless truth behind all religions. The Voice of the Silence is a prime example of this approach: it deliberately uses Eastern theological language but in a way that a student of Neoplatonism or Gnosticism can find correspondences. For instance, the ascent through the seven portals can be likened to the soul’s ascent through the seven planetary spheres in Neoplatonic mysticism, shedding impurities at each level. The “One Eternal and Absolute Reality” (Sat) is equivalent to the Neoplatonic One or the Gnostic pleroma of light. The insistence on conquering the illusion of separateness echoes the central Hermetic axiom of unity (“the All is One”). Even the motif of the soundless voice might remind a Western occultist of the “Voice of the Word” or Bath Kol in Kabbalistic tradition – a divine voice that does not speak in ordinary audible terms.

In sum, Blavatsky artfully interweaves multiple mystical strands. Buddhist Mahayana gives the text its framework of compassion and emptiness; Advaita Vedanta gives it metaphysical depth about the Self and illusion; mystical Christianity and Western esotericism provide parallel archetypes (Christ-like sacrifice, initiatory trials, the inner divine spark) that reinforce the universality of the lessons. This rich syncretism is not a hodgepodge but a deliberate tapestry illustrating what Theosophy calls the Ancient Wisdom Tradition. The text itself, as Blavatsky notes, contains ideas found “under different forms” in various scriptures . This is the hallmark of the Perennial Philosophy – truths expressed in many languages and symbols, but fundamentally the same. Therefore, The Voice of the Silence can be read as a nexus where different religious philosophies converge: it is Buddhist in ethic, Vedantin in metaphysic, and mystical-Christian in its emphasis on love and self-sacrifice, while also resonating with Western occult and Neoplatonic views on the soul’s ascent. Such a synthesis was Blavatsky’s project: to show that whether one speaks of Nirvana or Moksha or Union with God, the path to that supreme goal involves the purification of the lower self and the awakening of divine compassion. In doing so, she presents these esoteric teachings as not merely Buddhist or Hindu wisdom, but universal – belonging to all humanity’s spiritual heritage.

Relationship to Other Traditions

Parallels with Buddhist Mahayana (Yogācāra and beyond).

The Voice of the Silence is perhaps most directly comparable to the teachings of Mahayana Buddhism, and in particular it shares a kinship with texts and ideas from the Yogācāra and Madhyamaka schools. The emphasis on the Bodhisattva’s renunciation of Nirvana until all are saved is quintessential Mahayana. In Buddhist literature, this spirit is epitomized in works like Shantideva’s Bodhicaryāvatāra, which extols the resolve to bear the sufferings of the world out of compassion. Blavatsky’s fragment II reads like a poetic mirror of that ethos, asking “shall thou be saved and hear the whole world cry?” – a rhetorical question that could come straight from a Mahayana sutra admonishing a selfish arhat. Additionally, the concept of Pāramitās (perfections) in fragment III is directly lifted from Mahayana Buddhist practice; six or ten perfections are listed in texts like the Prajñāpāramitā Sutras or the Avatamsaka Sutra, and Blavatsky’s seven essentially cover the same ground (with a slight adjustment in enumeration). The Yogācāra influence is specifically hinted by Blavatsky’s mention that these teachings come from a school beyond the Himalayas where the “contemplative Mahayana (Yogacharya) schools” hold sway . Yogācāra Buddhism, also known as Cittamātra (Mind-only), teaches that all phenomena are manifestations of mind. This perspective resonates with The Voice of the Silence in its portrayal of the world as Mahā-Māyā (great illusion) and the need to conquer the illusions produced by the mind. The line “The Mind is the Slayer of the Real” could be interpreted in a Yogācāra sense: our unenlightened mind “slays” reality by superimposing its own delusions (vikalpa). Only through practices akin to Yogācāra meditation (which includes mastering Dhyāna and Samadhi, also mentioned in the text) can one perceive the alaya-vijñana (storehouse consciousness) and transform it to realize the Dharmakaya (ultimate truth body).

Moreover, The Voice reflects the Heart Doctrine or esoteric Buddhism, which Blavatsky equates with what Bodhidharma transmitted to China (the lineage of Ch’an/Zen) . This suggests parallels with Zen Buddhism as well, especially in the focus on direct insight beyond intellectualization. Zen often speaks of the “sound of one hand clapping” or hearing the voice of the inner Buddha in silence; these poetic zen-like elements find a Theosophical echo in Nâda, the Soundless Sound. The instruction to unite with the “Silent Speaker” within parallels the Zen idea of realizing one’s Buddha-nature in the silent mind. Additionally, the admonition to become deaf to both “roarings” and “whispers” in order to hear the inner voice recalls Zen and Mahamudra techniques of disregarding all thoughts, whether loud or subtle, to find the underlying awareness. While Blavatsky’s work is not Zen, it shares the intuitive, paradox-embracing flavor found in East Asian Mahayana mysticism.

It’s also worth noting parallels with Tibetan Buddhism (Vajrayana) since Blavatsky was inspired by Tibetan lore. The idea of initiation through graded stages and combating subtle obstacles is reminiscent of Tibetan Lamrim literature (step-by-step path) and tantric initiation rites. The term “Upādhyāya” for teacher and references to specific stages like Srotāpatti indicate familiarity with the Tibetan Buddhist monastic and scholastic framework. In Tibetan tradition, especially in the lojong (mind-training) teachings, great stress is laid on cultivating Bodhicitta (compassionate resolve) and the Pāramitās – which is exactly what The Voice of the Silence does in a concise way. Even the description of the final triumphant state where nature sings and a new Arhan is born could be compared to how Tibetan texts celebrate the Tulku or reincarnated bodhisattva’s appearance in the world for the benefit of beings. In short, The Voice of the Silence can be seen as a Western retelling of core Mahayana tenets: emptiness of self, universal compassion, and the rigorous path of self-perfection – ideals shared by Yogācāra philosophy and Mahayana praxis. It stands in relation to Mahayana much as a jewel reflects the colors around it: faithfully mirroring Buddhist wisdom while casting it in Blavatsky’s own esoteric idiom.

Parallels with Hindu Advaita Vedanta.

Underlying the Buddhist framework, there is a clear current of Advaita Vedanta and broader Hindu philosophy in Blavatsky’s text. Advaita (non-dualism) posits that the individual soul (Atman) is one with the absolute reality (Brahman), and that the perception of separateness is due to ignorance (Avidya) and illusion (Maya). The Voice of the Silence echoes these ideas frequently. For example, it speaks of the “Great Heresy” of believing in the separateness of a self , which directly parallels the Vedantic error of upādhi (false attribution of individuality) and the Buddhist concept of ātma-vāda (heresy of separateness) . The text’s call to “give up Self to Non-Self, Being to Non-Being” so that one may attain the All, is essentially an Advaitin instruction: surrender the limited ego to realize the Infinite Self (which from the ego’s perspective looks like a nothingness, but in truth is All-Being). This resonates strongly with the teachings of sages like Shankaracharya, who implore seekers to practice neti neti (“not this, not that”) – a letting go of all identifications until only the one true Self remains.

Blavatsky’s usage of Sat (absolute reality, truth) and Asat (false, unreal) is straight from Sanskrit philosophical discourse. In Advaita, one discriminates satya from mithya (real from apparent). The text’s metaphor of the world being a “Hall of Sorrow” filled with traps of illusion aligns with the Vedantic view of the world as ultimately duhkha (sorrowful) and anitya (impermanent), which must be transcended by realizing Brahman. Additionally, the idea of the soundless OM (AUM) humming throughout eternity is a Vedantic concept — the Mandukya Upanishad describes OM as the sound of Brahman and the substratum of all states of consciousness. Blavatsky’s footnotes reference the Nada-Bindu Upanishad and the mystical symbol of Hamsa (the swan) linked with the mantra AUM , further cementing the Vedantic connection. The paramitas themselves, while usually associated with Buddhism, can be likened to the Hindu shatsampat (six virtues like shama, dama – tranquility, self-control, etc.) required in Vedanta for the seeker of Brahman. Kshanti (patience) and Vairagya (dispassion, which is essentially Virag’) are classic virtues preached by Hindu yogis as well.

Moreover, the oneness underlying compassion in the text has an Advaitic root: if I am one with all, then loving others as oneself is simply a recognition of reality, not a moral duty imposed from outside. This is very much how Vedanta interprets compassion – it naturally flows from the experience of non-duality. In The Voice, when the disciple attains Prajñā (wisdom), he becomes a “Bodhisattva, son of the Dhyānis” – essentially a being who knows his unity with the divine (the Dhyani-Buddhas can be seen as divine intelligences, analogous to Hindu devas or aspects of Īśvara). This is comparable to the state of the jīvanmukta (liberated in life) in Advaita, who having realized Brahman, sees Brahman in all and thus works for the welfare of all without ego. The text’s instruction to act without any sense of separative self (echoed in phrases like “leave no further room for Karmic action” through perfect harmony ) parallels the Bhagavad Gita’s karma-yoga ideal of action without attachment to results and without ego, which leads to no new karma. In fact, one could say The Voice of the Silence teaches a kind of Karma-Yoga + Jnana-Yoga + Bhakti-Yoga combined: selfless action for others (karma-yoga), realization of the truth of the Self (jnana), motivated by love for all beings (bhakti in a universal sense). This integrative spiritual approach is deeply compatible with Vedanta, especially as interpreted in the broader Hindu tradition where these yogas are combined.

In summary, the relationship of The Voice of the Silence to Advaita Vedanta is seen in its non-dual worldview, its adoption of Sanskrit terminology and Upanishadic concepts, and its insistence on piercing the veil of illusion to recognize the one Self in all. A student of Vedanta can find in Blavatsky’s text a familiar call: to discern the Real from the unreal, to root out egoism (often described in Vedanta as the greatest enemy), and to realize Brahman-Ātman, here expressed as uniting with the “Higher Self” or the “One life.” The text thereby stands as a bridge between Buddhist and Hindu mysticism, demonstrating their complementary insights under the larger umbrella of Theosophy’s perennial wisdom.

Connections to Mystical Christianity.

Although The Voice of the Silence draws heavily on Eastern terminology, many of its spiritual principles resonate with Christian mystical and esoteric teachings. Blavatsky herself makes an explicit link by identifying the “Higher Self” – the inner divinity one contacts through the Voice of the Silence – with Christos of the Gnostics . In Gnostic and esoteric Christian terms, Christos is the indwelling Logos, the divine principle in each person (as opposed to the personal human figure of Jesus). Thus, when the disciple in the text seeks guidance from the “Silent Speaker” within, a Christian mystic might interpret this as listening to the voice of Christ in the heart. The Imitation of Christ in Catholic mysticism or the idea of the Inner Light in Quakerism similarly emphasize turning inward to find divine guidance. The soundless voice could be paralleled to the “still small voice of God” (from 1 Kings 19:12) that speaks in silence. Both imply that to hear the Divine, one must quiet the worldly clamor (recall the text: becoming deaf to the roarings and whispers of illusion ).

The ethic of compassion and self-sacrifice in The Voice is strongly consonant with Christian ideals of agapē (selfless love). The Bodhisattva’s pledge, “for others’ sake this great reward I yield” , finds an echo in St. Paul’s wish in Romans 9:3 where he expresses willingness to be “accursed” for the sake of his brethren’s salvation, or in Moses’ intercession offering to be blotted out of the Book of Life for his people (Exodus 32:32). The notion that “greater love hath no man than to lay down his life for his friends” is written into the Bodhisattva ideal – except here it is laying down even one’s heavenly reward. Christian saints often take vows to serve the poorest and most afflicted, effectively postponing their own “heaven” to bring light to others; this is a real-life Bodhisattva spirit. Mystical Christianity also teaches the purification of the soul through virtues (often known as the purgative way, the illuminative way, and the unitive way, which interestingly parallels the three halls: purification in the Hall of Learning, illumination in the Hall of Wisdom, and union in the realm of Sat). The seven portals could be compared to the seven deadly sins inverted into seven cardinal virtues in Christian tradition – each vice to be overcome by a corresponding virtue. For example, overcoming pride with humility, anger with patience, greed with charity, etc., is essentially what the Bodhisattva-in-training is doing with the paramitas. The Voice emphasizes Virāga (dispassion) and Kṣānti (patience), which are much the same as the Christian virtues of detachment and long-suffering meekness praised by mystics like St. John of the Cross.

Furthermore, the Chant of love that arises from Nature at the end , proclaiming peace to all beings, can be likened to the Christian vision of a redeemed creation. In the Bible, St. Paul speaks of all creation groaning and waiting for the manifestation of the sons of God (Romans 8:19-22). Here, when an Arhan is born (a son of the Dhyani-Buddhas), nature rejoices – a poetic way of saying the “curse” on nature (from mankind’s ignorance, in Christian mythos the Fall) is lifted a bit. Christian mystics like Hildegard of Bingen also described nature singing and rejoicing in divine harmony when a soul is in union with God. The esoteric Christian idea of theosis (divinization of the human, “becoming a god” by grace) aligns with the text’s statement that the final wisdom makes a man a god (a Bodhisattva, “son of the Dhyānis”) . Both traditions hold that the culmination of spiritual practice is to awaken the divine likeness within, effectively becoming united with the Divine in action and being.

Lastly, the structure of master-disciple and the language of discipleship resonate with Christian imagery of Christ and his disciples, or a spiritual father guiding a monk. While The Voice uses Sanskrit terms, one could substitute “Master (Higher Self)” with “Christ within” and “Disciple” with “devotee,” and the lessons would read very akin to a Christian mystical dialogue (similar to The Dialogue of St. Catherine where Christ speaks in her soul, or the counsel given in The Cloud of Unknowing about letting go of all creatures to grasp God). This demonstrates the universal quality of the instruction. Thus, The Voice of the Silence shares with mystical Christianity the call to inner listening, the primacy of love over ego, the transformation through virtue, and the ultimate union with the divine for the purpose of manifesting grace in the world. It’s a different symbolic language, but the symphony is in harmony.

Western Esoteric Traditions and the Perennial Philosophy.

Blavatsky’s Voice is deeply connected to Western esoteric thought in that it embodies the principle of the Perennial Philosophy – the notion that a single truth underlies all spiritual traditions. Western esotericists from the Renaissance onward (like the Hermeticists, Rosicrucians, and Freemasons) often attempted to synthesize different religious symbols, seeking an underlying prisca theologia (ancient theology). Blavatsky’s work can be seen as a continuation of that quest, but with far greater input from Eastern wisdom. The result is a text that Western occult students quickly recognized as akin to their own teachings, only in Oriental garb. For example, the concept of an inner Master or Higher Self that The Voice emphasizes is comparable to the Holy Guardian Angel in Western Hermeticism (as in the teachings of the Golden Dawn or Aleister Crowley’s system), which is the inner divine guide one must contact. The process of purifying oneself and mastering virtues to become one with the Higher Self is reminiscent of the alchemical Great Work: turning the lead of base nature into the gold of spiritual illumination. Each portal conquered is like a stage in the alchemical transmutation or a degree in a mystery school initiation.

The number seven is highly significant in Western esotericism (seven planets, seven days, seven virtues/vices, etc.), so the choice of seven portals speaks to a shared symbolic language. A Western occultist might map the seven portals to the Qabalistic Tree of Life – perhaps to the seven lower Sephiroth that the aspirant must balance and perfect before reaching the supernal triad (which could correspond to the realm of Sat or the final enlightenment). Each paramita could be aligned with certain Sephiroth qualities (for instance, Dāna with Chesed (mercy), Śīla with Tiphereth (beauty/harmony), Kṣānti with Geburah’s higher aspect of patience under discipline, etc.). This kind of syncretism was likely intentional on Blavatsky’s part, as she was aware of Kabbalistic and Hermetic systems and saw them all as reflections of the same septenary law.

Another Western parallel is the Neoplatonic tradition. Plotinus taught about ascending from the material to the divine Intellect and finally to the One, through purification (similar to passing the Hall of Learning to Wisdom) and contemplation (Dhyāna) leading to ecstatic union (henosis). The Voice’s journey can be read as a Neoplatonic ascent – starting from the cave of illusion (echoing Plato’s cave, or the Hall of Ignorance) and rising to the vision of Reality (the realm of Sat, analogous to the One or the Good). Neoplatonists also emphasized virtue as the first step in the spiritual ascent (as does The Voice), and they too honored the concept of a guiding daemon or higher genius (compare with Higher Self).

The Perennial Philosophy aspect is explicitly acknowledged by Blavatsky when she notes the common source and similarity of these teachings to many traditions . The Voice of the Silence in its very structure – combining elements of Buddhist, Brahmanical, and Gnostic thought – is a demonstration of the perennial wisdom that Blavatsky believed in. In Western esoteric circles, this would have bolstered the idea that Eastern mysticism and Western mysticism were simply using different symbols to describe the initiate’s path. Indeed, many later Theosophists and occultists (like Alice Bailey, or even non-Theosophists like Aldous Huxley, author of The Perennial Philosophy) drew on The Voice of the Silence as evidence of a universal core of truth. H.P. Blavatsky’s synthesis can be seen as a fulfillment of the Enlightenment-era dream of a Universal Religion or Universal Wisdom – not by creating a new creed, but by showing a pathway that any sincere seeker from any tradition could walk. Whether one comes from a background of Kabbalah, Sufism, Christian mysticism, or Hinduism, one would find familiar landmarks in the journey described in The Voice. Thus, in relation to Western esoteric traditions, Blavatsky’s text is less about borrowing specific Western occult ideas (though parallels exist) and more about affirming the common journey those traditions speak of. It stands as a literary testament to the Perennial Philosophy: the idea that there is a single mountain with many paths, and that the guidelines for climbing – ethical purification, meditation, divine love, and the ultimate union with the One – are fundamentally the same despite cultural variations. In bridging East and West, The Voice of the Silence enriched Western esotericism, offering it a profound poetic scripture of the perennial wisdom from an Eastern source, yet universally applicable.

Conclusion

The Voice of the Silence delivers a timeless spiritual message that transcends the particulars of any one tradition: it is a call to inner awakening and compassionate action. At its heart, the text teaches that true enlightenment is attained by purifying one’s mind of illusion, tuning in to the silent voice of the divine within, and dedicating oneself to the welfare of all beings. This triune message – self-purification, inner realization, and selfless service – is the essence of what Blavatsky presents as the highest esoteric path. The journey it describes is deeply personal and at once universal: each disciple must walk the path of their own soul, conquering their unique inner “demons” and passing through trials of character, yet the goal is the same for all – the emergence of the latent divinity and the blossoming of divine love in the human heart.

Even today, well over a century since its publication, The Voice of the Silence remains profoundly relevant to esoteric practitioners and spiritual seekers. Its verses continue to be studied and meditated upon in Theosophical circles and beyond. For those who are already familiar with Eastern philosophies, the text provides a poetic synthesis that can deepen understanding through contemplation. For Western spiritual aspirants, it serves as an accessible gateway to Eastern mysticism, presenting complex ideas in a distilled, heart-centric form. The modern seeker, confronted with a world of distraction and ego-driven pursuits, can find in Blavatsky’s words a gentle but firm directive to turn inward: “Before the Soul can hear, the image of man has to become as deaf to the external as to the internal voices of illusion”, and “before the Soul can comprehend and remember, it must be united to the Silent Speaker” . Such instructions are perhaps even more urgently needed in our noisy, fast-paced era. The text is not merely to be read, but to be lived – it invites one to practice meditation (Dhāraṇā/Dhyāna), to cultivate virtues in daily life (the paramitas as practical ethics), and to adopt a worldview of unity and compassion.

Blavatsky’s synthesis of wisdom traditions in The Voice of the Silence can be seen as a pioneering effort in what is now a much more interconnected global spiritual landscape. Her work anticipated the present-day interest in comparative religion and interfaith dialogue by demonstrating an intrinsic harmony between the highest teachings of East and West. The concept of a perennial wisdom – that all traditions share the same ultimate truth – is exemplified on every page, as Buddhist, Hindu, and mystical Christian ideas flow into one another seamlessly. This encourages modern esotericists to look beyond sectarian boundaries and find common ground. It’s a reminder that the spiritual quest is one, whether one uses the language of Bodhisattvas, Yogis, or Saints.

In conclusion, The Voice of the Silence stands as a beacon of the inner life – a poetic scripture of the soul that continues to inspire and guide. Its enduring power lies in the depth of its philosophical insight and the sincerity of its compassionate vision. Blavatsky managed to condense a vast spiritual heritage into a series of gem-like verses that both educate and enkindle the intuition of the reader. The final note of the text rings with hope and benediction: “A new Arhan is born… Peace to all beings.” . This is the ultimate aim – that each of us may awaken the Arhan or Christ within and become a source of peace to all. The Voice of the Silence thus continues to whisper its eternal counsel in the hearts of those “few” who aspire to climb the mountain of spiritual attainment, reminding them that the summit is reached not by self alone but through the self forgotten in service of the All.