Table of Contents

Introduction

What defines the nature and behavior of women, and how have these traits played out over the sweep of history? It’s a question that has provoked philosophers and scientists alike. In the 19th century, philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer offered a scathing assessment: he described women as “childish, short-sighted…big children all their lives” who “always see only what is near at hand” (Arthur Schopenhauer. On Women “1865 | by Theodor Svedberg | Medium). Schopenhauer argued that women are inherently present-oriented, emotional, and manipulative – a provocative lens that, however misogynistic, raises deeper questions. Are there kernels of truth in his caricature that align with historical patterns and evolutionary pressures? How have women wielded influence in societies that often denied them overt power? And how are modern technologies reshaping age-old gender dynamics?

This long-form exploration takes a fearless and analytically rigorous look at women’s behavior and social roles from ancient civilizations to the digital age. We will use Schopenhauer’s contentions as a jumping-off point to examine broader patterns – from evolutionary divergences between men and women in time orientation and reproductive strategy, to the indirect forms of power women have exercised through emotional and social means. We’ll trace women’s roles through antiquity, agrarian eras, industrial society, and into today’s online world. Along the way, we analyze how key innovations – notably contraception and social media – have upended incentives and outcomes. The goal is not to vindicate Schopenhauer’s 19th-century chauvinism, but to contextualize elements of it against the evidence of history, biology, and contemporary trends. In doing so, we can better understand which gendered behaviors are evolutionary holdovers and which are shaped by shifting technology and culture.

Schopenhauer’s Provocative Lens on Womanhood

Schopenhauer did not mince words in critiquing women. In his 1851 essay “On Women,” he asserts that “women remain children all their lives, for they always see only what is near at hand, cling to the present… and prefer trifling matters to the most important”. In his view, a woman’s mind was narrowly focused on immediate, personal concerns – family, love, and petty domestic affairs – whereas a man’s reason allowed him to ponder past and future, giving him wider ambition and anxiety. Schopenhauer even cynically remarked that Nature equips women with a brief bloom of youthful beauty “at the expense of the rest of their lives” in order to “ensnare the fantasy of a man” and induce him to provide for her and her offspring. Once her reproductive role was secured, he noted, a woman’s beauty would fade – just as a female insect loses her wings after mating.

Such claims paint women as inherently dependent and cunning creatures of the moment. According to Schopenhauer, because women are the physically weaker sex, “Nature has not destined them… to be dependent on strength but on cunning; this is why they are instinctively crafty”. He went so far as to say women have an “ineradicable tendency to lie” and a natural gift for dissimulation – concealing their true feelings or intentions – as their evolutionary weaponry. In short, where men wield brute force or reason, women, he argued, survive by manipulation, charm, and deception.

It’s a harsh and one-sided portrait. Yet, as a “provocative lens,” Schopenhauer’s perspective usefully highlights certain themes that we will see echoed (in more nuanced form) in both evolutionary science and historical reality. The idea that women might be more attuned to immediate concerns and indirect influence, for example, has parallels in evolutionary psychology’s understanding of sex differences. And the claim that women exercise power through subtle or emotional means rather than overt dominance resonates with how many women in patriarchal societies have actually navigated power structures. Before turning to history, then, we examine the evolutionary roots that underlie some divergent tendencies in male and female behavior.

Evolutionary Origins of Divergent Male and Female Behavior

Human evolution has shaped men and women with different reproductive imperatives and survival strategies. Biologically, females invest far more in producing each offspring (pregnancy, childbirth, nursing) than males do. This fundamental asymmetry in parental investment has far-reaching behavioral consequences. Evolutionary biologist Robert Trivers noted that the sex which invests more in offspring will be choosier about mates, while the less-investing sex will compete for access to the high-investors. In our species, this generally meant women evolved to be more selective and risk-averse in mating, seeking partners who could provide and protect, whereas men evolved to compete for mating opportunities and status ( Evolved but Not Fixed: A Life History Account of Gender Roles and Gender Inequality - PMC ).

Time orientation may partly stem from these roles. A mother’s paramount concern across evolution was the immediate survival and well-being of her children – an urgent, present-focused orientation. A father, while certainly concerned for family in the present, could increase reproductive success by also taking risks or planning long-term (e.g. forging alliances, stockpiling resources) to secure future advantages. Schopenhauer’s observation that women “live more in the present than a man” aligns with this idea. He even conceded that a woman’s present-mindedness lends her a certain “cheerfulness” and sobriety in judgment – seeing things “no more… than is really there” – whereas men’s far-ranging ambitions can lead them to anxiously exaggerate or pursue abstract causes. In evolutionary terms, one might say men followed more future-oriented strategies (hunting large game over days, strategizing warfare, accumulating wealth for posterity), whereas women, burdened with pregnancy and nursing, optimized for immediate security and nourishment of their offspring.

Reproductive strategies also diverged. A man could, in theory, father dozens of children with different women if circumstances allowed, favoring a more “quantity-driven” strategy in sexual behavior. A woman can bear only a limited number of children in her lifetime and each child entails enormous cost; thus women’s strategy skewed toward “quality-driven” reproduction – investing heavily in a few offspring and choosing mates wisely. Biologically, women evolved to prefer males who could offer resources, protection, or good genes, since the “costs of a present-oriented reproductive strategy” (having many children in quick succession) fell disproportionately on them. If a woman had too many offspring too rapidly, she would struggle to care for them without support, leading to high child mortality. Men, by contrast, competed with each other for mating opportunities, which favored traits like physical aggression, risk-taking, and status-seeking. Anthropologists note that in primitive societies male competition often manifested in raiding and warfare, sometimes involving capture of women as “trophies”. The evolutionary “wiring” of men thus leans toward direct competition and hierarchy – behaviors that require projecting power into the future – while women’s wiring emphasizes nurturing and careful mate selection, anchored in the realities of the present.

Modes of power acquisition followed from these differences:

- Direct vs. Indirect Power: Males throughout human evolution gained reproductive success largely by attaining dominance or status – becoming the leader, the best hunter, the warrior who could command or impress others. Physical strength and direct competition were their tools. In contrast, females, less able to rely on brute force, often had to exercise influence indirectly. Evolution endowed women with keen social intelligence and emotional savvy, which could translate into “cunning” and negotiation skills. As Schopenhauer put it metaphorically, “all the power… given to man in the form of bodily strength and reason has been conferred on woman in [the form of] dissimulation”. A woman’s traditional weapons were not fists or spears but words, charm, allure, and alliances. This doesn’t imply women are “deceptive by nature” as Schopenhauer claimed; rather, under conditions where overt power was denied, subtle strategy was a rational route to achieve goals. We will see this pattern repeatedly in history – from queens whispering counsel behind thrones to modern social media influencers swaying hearts and minds.

- Risk and Competition: Men’s evolutionary role in high-risk endeavors (big-game hunting, inter-tribal conflicts) selected for higher risk tolerance and competitive drive. Women, carrying unborn life and tending the young, often had more to lose from reckless risk. This likely yielded more cautious, collaboration-focused behavior among women. Studies indeed show men are generally more risk-prone than women, presumably due to the long history of intense male intrasexual competition for mates and status (Sex differences in risk attitudes and short-term orientation and their ...). Women’s competition didn’t vanish – but it took forms that were less openly violent, such as social rivalry, gossip, and competing for male commitment through fidelity or attractiveness rather than force.

- Emotional and Social Skill: Because human offspring survive best with cooperative parenting, evolution also forged significant overlap and complementarities between the sexes. Women and men formed pair-bonds; the most successful men in reproduction were those who provided for their mates and offspring over the long term. Thus, traits like male parental investment, female empathy, and social cohesion became part of our species profile. Women tend (on average) to excel in empathic and verbal skills, facilitating their role as caregivers and community builders, whereas men (on average) show strengths in spatial and physical skills useful for provision and defense. Modern psychology finds these differences are statistical and heavily influenced by culture, but their roots trace back to survival strategies that once made sense.

In short, eons of evolution equipped women and men with different tilts in behavioral tendencies – not absolute determinants, but predispositions. Women’s evolutionary role emphasized stability, immediate needs, and kinship bonds, while men’s emphasized acquisition, future planning, and competitive achievement. Bearing this backdrop in mind, we can better understand how, as human societies developed from the Stone Age to modern states, female behavior adapted and female influence manifested in distinct ways. Next, we turn to history to see how women navigated their roles in changing economic and social systems – often in line with, but sometimes in defiance of, these evolutionary inclinations.

Women in Antiquity: Hearth and Home in Early Civilizations

In prehistoric hunter-gatherer bands, scholars believe that gender relations were relatively egalitarian compared to later societies. With no permanent property to pass on and survival dependent on group cooperation, women in nomadic foraging groups could command respect as gatherers (providing a substantial portion of food) and as kin who forged alliances between families. Anthropological studies of modern hunter-gatherers suggest women in such societies could leave an unsatisfactory partner and return to their kin with fewer repercussions. Without fixed assets or enforced monogamy, men had less means to control female sexuality – a woman unhappy with a mate could, in essence, “vote with her feet” and find protection among relatives or a new partner. This isn’t to idealize prehistoric life – physical power still mattered and women’s childbearing made them vulnerable – but there was a notable lack of rigid patriarchal institutions in many early human communities.

The rise of agriculture and settled civilizations dramatically changed the equation. With farming around 10,000+ years ago, humans began accumulating surplus wealth – crops, herds, land – which for the first time could be owned and inherited. This development set the stage for formalized patriarchy. Men’s superior average strength made them the warriors and plowmen defending territory. As villages grew into fortified towns, frequent conflict over land and livestock meant those who fought (mostly men) gained prestige and control over resources (Analysis: How did the patriarchy start – and will evolution get rid of it? | UCL News - UCL – University College London). Over generations, men came to monopolize wealth and power in these agrarian societies, and they devised cultural norms to solidify that hold.

One pivotal change was the emphasis on paternity certainty. In order for men to pass property to their own offspring, they sought to tightly control women’s reproductive lives. The result across many cultures was a confinement of women to the domestic sphere, often coupled with social or even physical constraints on their mobility and sexuality. Historian Gerda Lerner and others have pointed out that as wealth and stratification increased, “young women were [treated as] the resource in demand”, valued for their ability to produce heirs. Marriage became a contract of alliance and property: fathers “gave” daughters to grooms (often in exchange for a brideprice or dowry), and wives were expected to be chaste and loyal to ensure the lineage’s purity. In ancient Mesopotamia and classical Greece, a respectable woman’s domain was her home; in many cases she could not own major property or participate in public decisions. The laws of Hammurabi (Babylon, ~1750 BCE) and Athenian law alike treated women essentially as wards of their fathers or husbands.

Despite these constraints, women in antiquity were far from passive. Within the household (the oikos in Greek), the wife matriarch wielded considerable authority over children, slaves, and domestic economy. Furthermore, a few exceptional women did rise to direct power, usually through royal bloodlines. Queens and consorts could influence empires from behind the scenes – for example, Queen Nefertiti in Egypt (14th century BCE) co-ruled with her husband, and later, Cleopatra VII of Ptolemaic Egypt (1st century BCE) directly ruled and famously leveraged her political and personal wiles to align with Roman leaders Julius Caesar and Mark Antony. These, however, were rare cases. More typical was the situation in Republican Rome: women of the elite managed estates and formed networks (such as Claudia and the women in Julius Caesar’s family who were said to sway politics indirectly), but they could not vote or hold office. Across ancient civilizations – from India to China to the Americas – the dominant pattern was that women’s formal role centered on marriage, motherhood, and managing the home, while public life was a male arena.

Crucially, though, this did not mean women lacked influence. They simply had to exercise it through different channels. Here we begin to see the historical analogues of what Schopenhauer called women’s “indirect methods” of power. In ancient courts, a wise wife or mother of a ruler could “wheedle” or counsel her husband or son toward certain decisions. For instance, in the Hebrew Bible, Queen Esther saves her people by shrewdly appealing to a king’s emotions at a banquet; in ancient India, the female sages Gargi and Maitreyi were respected for their wisdom, though they had no official position. Informal power – via persuasion, charm, even seduction – was often the only avenue open to women in strictly patriarchal systems. As we move to the medieval and agrarian era, this pattern became even more pronounced.

The Agrarian Age: Patriarchy Entrenched and the Domestic Sphere

Throughout the long agrarian era (roughly from the fall of Rome through the late Middle Ages and early modern period in Europe, with parallel eras elsewhere), the vast majority of people lived in rural communities where life revolved around farming. Women’s roles in these traditional societies were extremely demanding physically – peasant women toiled in fields, ground grain, spun cloth, bore and raised many children – yet their labor was defined as domestic duty, supporting the male-headed household. A woman’s social identity was typically as someone’s daughter, wife, or mother, under the protection and authority of male kin. The patriarchal family was the basic unit of production and social order.

Patriarchy during this era was often buttressed by religion and custom. In medieval Europe, for example, the Christian Church taught the model of the husband as the head of the household and the wife as the obedient “helpmeet.” Influential texts like Aristotle’s politics (rediscovered in the Middle Ages) argued that men are by nature superior in reason and leadership, fitting them for the public sphere, whereas women’s virtue lay in modesty and managing the private realm. Similarly, in Song dynasty China, Confucian norms idealized women’s submission, leading to practices like foot-binding among the elite to physically enforce women’s seclusion and dependence. Across many agrarian cultures, we see versions of purdah (veiling and secluding women), intense sexual double standards (harsh punishments for female infidelity, relative tolerance of male promiscuity), and legal disenfranchisement (women generally could not inherit land on equal terms with male siblings, for instance). These norms aimed to guarantee paternity and lineage continuity in an era when wealth was tied to land and bloodline.

Yet, within these constraints, women continued to find ways to assert themselves and contribute to their communities. In many places, women were economic partners in family enterprises – running shops, brewing ale, or engaging in cottage industries – even if the law regarded the husband as the owner of all property. Women’s skill in “household management” was not trivial: managing food stores to last the winter, making clothing, tending to livestock, and raising children required intelligence, planning, and resourcefulness (qualities often undervalued by male chroniclers of the time). And significantly, some women in agrarian societies gained cultural or spiritual authority. The Middle Ages saw abbesses like Hildegard of Bingen wield influence in intellectual and religious spheres; women mystics and saints were revered by the masses. In West Africa, queen mothers and female chiefs had recognized roles in advising kings. Even where formal structures were male-dominated, smart leaders realized they could not entirely ignore the voices of half the population, especially on issues of family and morality.

The agrarian age also continued the pattern of indirect female power in its most intimate form. As one historian quipped, “the bedchamber was sometimes the real throne room.” Let us delve deeper into how women exercised power through emotional, aesthetic, and social means when direct avenues were closed.

Indirect Power: Women’s Influence Behind the Scenes

Throughout history, women have often had to be “power behind the throne” rather than on it. Lacking formal authority, they learned to employ emotional intelligence, social networking, and yes, sometimes manipulation to achieve their aims. The chronicles of royal courts, in particular, are filled with tales of wives, mothers, sisters, and mistresses who swayed the course of events not by decree or sword, but by counsel, charm, or coercion in private.

A clear summary of these dynamics comes from medieval history: “Most women who wield indirect power are those with exceptionally intimate ties to powerful men: wives, mothers, daughters and mistresses… The main methods used by them to exercise such influence are wheedling, nagging, the giving or withholding of sexual favours, and the bearing of sons.” (Medieval women and power – Magistra et Mater). In other words, a woman’s proximity to a man in power (be it a king, lord, or any influential male) could grant her a channel to voice opinions or subtly push an agenda. Queens like Eleanor of Aquitaine (12th century) navigated the politics of two kingdoms (France and England) by advising and occasionally contriving against kings; the Dowager Empress Cixi in 19th-century China started as a concubine but effectively ruled China for decades by controlling her son and later her nephew (both nominal emperors). These women operated in a sphere of informal power that relied on personal relationships and often sexual or maternal leverage.

It must be noted that such indirect power, while real, was available only to a small minority of women – typically those in elite circles – and it came at a cost. The historian Magdalene Adelman observes that “women’s gaining indirect power has traditionally involved… the reduction of their own selves to [their] bodies” – i.e. using beauty, sexuality or fertility as currency – and that this power “tends intrinsically towards the deceitful, if not actively toxic.”. A woman who pursued influence through seduction or “nagging” could easily be painted as a villain (think of biblical Delilah or the trope of the “scheming queen”). Indeed, anti-feminist commentators through the ages often argued that women didn’t need legal rights because they held “informal power” over men by manipulating their desires. This claim was used to downplay the injustices women faced – effectively saying “you secretly rule us from behind the scenes, so why demand equality?”

Nonetheless, informal influence was one of the few tools available to women in strictly patriarchal contexts, and many wielded it adeptly. They cultivated emotional bonds – a wise queen might become her husband’s most trusted confidant, or a favorite daughter might soften a father’s harsh ruling. They capitalized on aesthetic appeal and grace – from the courtesans of Renaissance Venice to the geishas of Edo Japan, women trained in the arts of beauty and conversation could influence powerful male patrons’ opinions on matters of art, policy, or patronage. They also forged women’s networks: within harems or courts, women often collaborated, sharing information and uniting to advance their children’s prospects or to counter rivals. This social strategizing was a form of survival and agency given the constraints – a point often missed by those who reduce it to mere “gossip” or “pettiness.”

Schopenhauer’s claim that woman’s weapon is “cunning” and man’s weapon is force has a dark resonance with these historical patterns. While he meant it derisively, one can reinterpret it as meaning that women historically had to be more discerning and tactful in pursuit of their goals. The prevalence of dissimulation (discreet, covert action) among disenfranchised groups is not a female flaw per se, but a reflection of disenfranchisement itself. When one cannot confront power directly, one learns to navigate indirectly. Thus, the emotional and social means by which women exerted power – whether consoling a king to calm his wrath, “nagging” a husband to spend money on the children, or forming alliances with other women in the shadows – were adaptive strategies in a world that gave them few formal outlets.

Of course, indirect power could never fully compensate for lack of rights. Most women remained largely at the mercy of their fathers’ or husbands’ decisions. And yet, by the end of the agrarian era, cracks in the patriarchal order were beginning to show. The seeds of change came from multiple directions: the rise of market economies, the influence of Enlightenment ideas about natural rights, and women’s own persistent efforts to assert their voices. The stage was set for the industrial age, which would dramatically upend the age-old domestic order.

The Industrial Age and the Separate Spheres

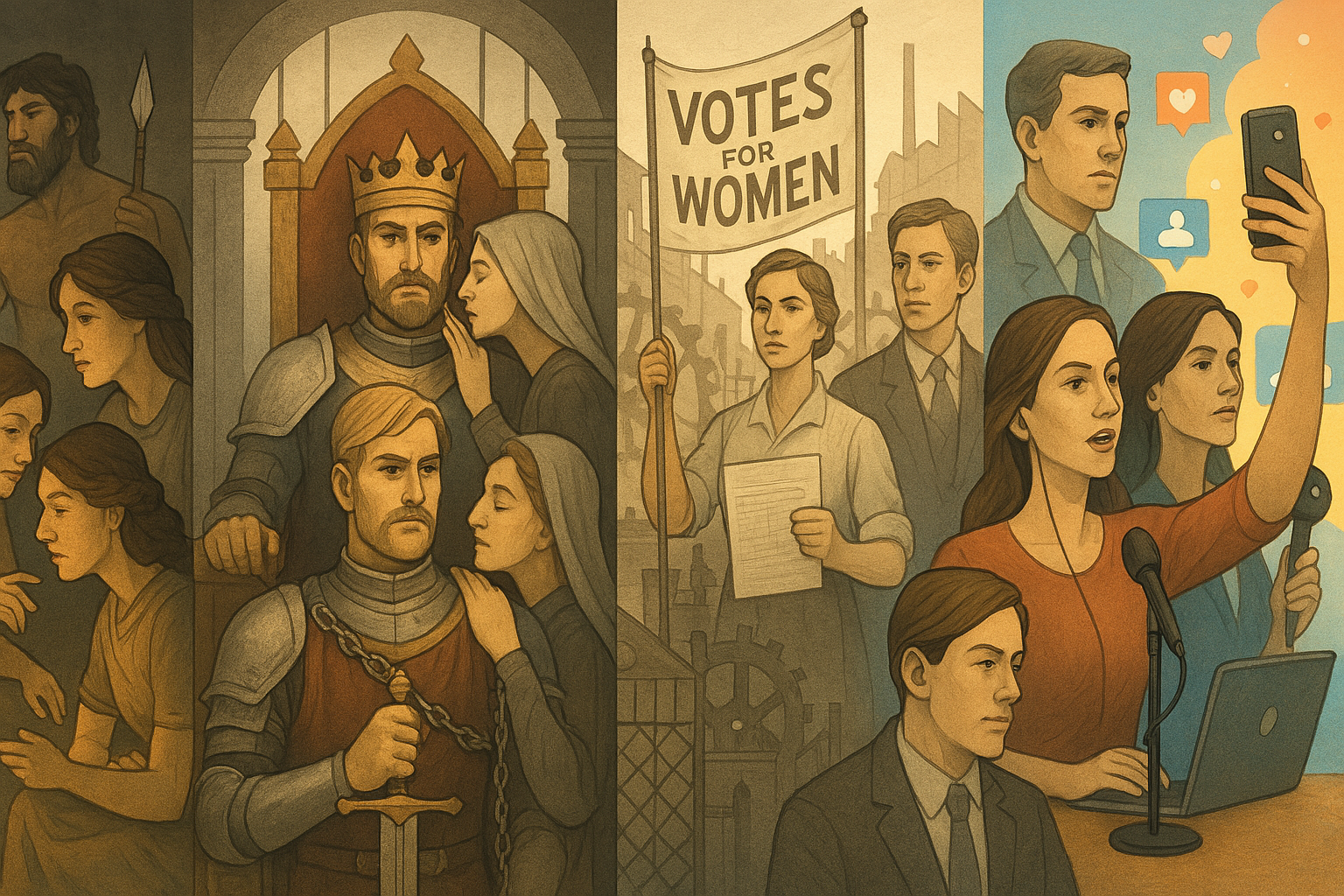

The Industrial Revolution (late 18th through 19th century) transformed society from a primarily agrarian world of villages into an urban, industrialized one. This upheaval had complex effects on women’s roles – in some ways opening new opportunities, but in other ways reasserting gender divisions in a new form. The iconic 19th-century gender ideology is often summed up as the doctrine of “separate spheres.” Under this ideal, men and women occupied distinctly different domains of life: men belonged in the public sphere of paid work, politics, and commerce, while women were relegated to the private sphere of home and family. This was a departure from earlier agrarian households where husbands and wives had often labored side by side on a farm or in a family business. Now, with factories and offices drawing men into wage labor away from home, middle-class women were idealized as domestic angels – the homemakers, nurturers, and moral guardians of the family.

“The Sinews of Old England” (1857) by George Elgar Hicks portrays the Victorian ideal of separate spheres: the husband, equipped with a scythe, steps out to labor in the fields (public sphere) while the wife clings to him at the threshold of their home with a child by her side (private sphere). This 19th-century imagery captured the widespread belief that a woman’s proper place was in the domestic realm, providing a restful haven for the breadwinning husband . The Industrial Revolution had pulled men into workplaces outside the home, and in response society glorified women’s role in child-rearing, housekeeping, and maintaining religion and virtue in the household (Separate spheres - Wikipedia).

For the emerging middle class in Europe and America, the separate spheres model was a status symbol – if a wife could afford not to work, it signified the family’s economic success. Advice literature of the 1800s is replete with exhortations that a “true woman” should be pious, pure, submissive, and domestic, focusing her energies on creating a stable, loving home (25e. The Emergence of "Women's Sphere" - USHistory.org). Men, by contrast, were cast as naturally aggressive, rational, and worldly, suited to competition in business and politics. This ideology certainly reinforced patriarchy – it confined women’s influence to the home and justified denying them political rights on the grounds that public life was beyond their sphere. It is no coincidence that during this era, women were largely barred from voting, higher education, and most professions. As one example, when the French Revolution erupted in 1789 with cries of “liberty and equality,” women like Olympe de Gouges who demanded equal political rights for women were met with hostility. By the mid-19th century, across Europe and America, the cult of domesticity was the dominant cultural norm, and any woman who stepped too far into male domains risked social censure.

However, the reality of industrial society was more complicated than the ideal. Working-class women did not have the luxury of a separate domestic sphere – they often labored in factories, mills, or as servants to make ends meet. In England’s early textile mills, for instance, young unmarried women made up a large portion of the workforce. These laboring women experienced a different aspect of industrialization: grueling long hours, but also a taste of wage-earning independence. Meanwhile, the very forces of modernization that entrenched separate-sphere ideology also sparked the first organized movements for women’s rights. Enlightenment philosophy had planted the idea that rights should be universal. Visionaries like Mary Wollstonecraft (who penned A Vindication of the Rights of Woman in 1792) argued that women were not inherently inferior but appeared so only through lack of education and opportunity. Early feminists pointed out the hypocrisy that democratic revolutions expanded male suffrage but left women voiceless.

By the late 19th century, the winds of change were unmistakable. Women were pursuing higher education (the first women’s colleges opened; by the 1870s some universities admitted women). They entered professions like nursing and teaching, carving out a recognized social role as caretakers and educators outside the home. The suffrage movement gained momentum on both sides of the Atlantic, as women activists campaigned relentlessly for the right to vote and for legal reforms. This was the era of Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton in the U.S., Emmeline Pankhurst in Britain – formidable women who directly challenged the notion that politics was a male-only sphere.

Still, many barriers remained. Culturally, society was uneasy about women who strayed from the domestic ideal. An unmarried woman who focused on career or activism might be derided as a spinster or unwomanly. In most countries, women did not gain the vote until the early 20th century (for example, 1920 in the U.S., 1918/1928 in the U.K.). But a dramatic catalyst arrived in the early 20th century that accelerated change: two World Wars.

Twentieth-Century Upheavals: Suffrage, World Wars, and the Pill

The 20th century brought seismic shifts in women’s behavior and societal roles – arguably more change in 100 years than in the previous thousand. Key drivers were women’s political emancipation, their mass entry into the workforce during wartime, and technological innovations like modern contraception that fundamentally altered reproductive life.

Women’s Suffrage Achieved: The long campaign for voting rights succeeded in many nations in the 1910s and 1920s. As women began to vote and even hold public office, their influence on policy became tangible. Evidence from historical research indicates that bringing women into the electorate affected governance priorities. For instance, one study of Switzerland’s late adoption of women’s suffrage showed that afterward social welfare spending increased by 28%, suggesting that women voters placed greater emphasis on education, health, and the safety net (Women's Suffrage and the Growth of the Welfare State - jstor). Similarly, in the United States, women’s suffrage has been linked to increased public health spending and legislation favoring child welfare. In short, female enfranchisement started to inject what one might term more “nurturing” or stability-oriented values into public policy – a point we will revisit.

World War I and II – Women to the Workforce: When World War I (1914–1918) and later World War II (1939–1945) conscripted tens of millions of men into the military, the home front economies desperately needed labor. Women responded by entering traditionally male jobs on an unprecedented scale. During World War II, for example, some 5 to 6 million American women joined the workforce for the first time, taking up roles in factories, shipyards, and offices. By 1944, women held one-third of all manufacturing jobs in the U.S., and the overall female labor force participation rate jumped from 27% pre-war to 37% of the workforce (Women of the WWII Workforce: Photos Show the Real-Life Rosie the ...) (Table of Statistics on Women in the World War II Era Workforce · SHEC). The iconic image of “Rosie the Riveter” – the female factory worker in overalls flexing her bicep – symbolized this temporary but transformative shift.

(File:Rosie the Riveter (Vultee) DS.jpg - Wikipedia) A real-life “Rosie the Riveter” at work: A female war-worker operates a heavy drill in a U.S. aircraft factory (Tennessee, 1943). Such images proved that women could perform strenuous industrial labor as well as men. During World War II, with men fighting overseas, women in many countries entered fields from manufacturing to engineering to government service. In the U.S., the female labor force grew by 50% between 1940 and 1945 ([PDF] Women Workers in World War II - HistoryLink.org). Women filled roles as welders, mechanics, and munitions assemblers, often earning their first paychecks. This experience gave many a new sense of confidence and economic independence.

When the wars ended, millions of women were pushed or encouraged to return to domestic life to make way for returning servicemen in the job market. The late 1940s and 1950s thus saw a reassertion of traditional gender roles in some respects (the “happy homemaker” archetype in post-war suburbia). But the genie was out of the bottle: women had proven their capability in all manner of work, and many had gotten a taste of financial independence. This set the stage for the second-wave feminism of the 1960s and 1970s, which fought not just for legal rights but for broader social equality – employment, sexual freedom, an end to pervasive sexism.

The Sexual Revolution and The Pill: Perhaps no technological advance has been more revolutionary for women’s behavior than the invention of reliable birth control pills. Enovid, the first oral contraceptive, was approved in 1960, and suddenly women had near-complete control over if and when to conceive – something totally unprecedented. By the mid-1960s, millions of women (even young, unmarried women) were on “the Pill,” and it profoundly decoupled sexual activity from reproduction. Women could engage in sex without the looming “fear of pregnancy” that had haunted earlier generations (How The Approval Of The Birth Control Pill 60 Years Ago Helped Change Lives : NPR). One woman who came of age in the 1960s said of the Pill’s arrival, “It was like going from night to day… I had control, I had choice. It gave me a whole new lease on life.”. With fertility no longer left to chance or the whims of abstinence, women could postpone marriage and childbirth to pursue higher education and careers. Indeed, economists have credited the Pill with enabling women’s surge into professional fields and even narrowing the gender pay gap; one analysis estimated that one-third of women’s wage gains since the 1960s were attributable to access to oral contraceptives (Birth Control in America: A Brief History of Contraception).

Beyond careers, the social effects of widespread contraception were dramatic. The late 1960s saw the so-called Sexual Revolution, a loosening of sexual mores. Feminists at the time argued that women, like men, enjoy sex and have sexual needs, and that women should be free to express their sexuality without shame (The Pill and the Sexual Revolution | American Experience | Official Site | PBS ). The Pill was often blamed (or praised) for this revolution. By removing the risk of unwanted pregnancy, it “allowed women to separate sex from procreation”, meaning single and married women alike could have sex “anytime, anyplace, with anyone” without fear of getting pregnant. To social conservatives, this heralded chaos – one commentator in 1968 even warned the Pill’s impact might be “more devastating than the nuclear bomb” on society’s moral fabric. But from a liberation perspective, it meant women could assert control over their own bodies and desires, instead of being bound by the old double standard (where men sowed wild oats but women who did the same were ruined).

There were unintended consequences as well. Freed from the old constraints, premarital sex and divorce rates rose in the 1970s, which some saw as evidence of social decay, but others interpreted as people (especially women) no longer trapped in unhappy marriages. Birth rates in developed countries plummeted with the combination of contraception and women’s changing priorities – a trend that continues today. By 2024, fertility rates in so many countries had dropped below replacement (2.1 children per woman) that demographers project over 75% of countries will be in population decline by 2050 without immigration. This historic shift is largely due to women choosing to have fewer children, thanks to education and contraceptive access reducing high-fertility pressures (The Lancet: Dramatic declines in global fertility rates set to transform global population patterns by 2100 | Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation). In effect, technology decoupled sex from reproduction to such a degree that societies now face the opposite problem of what worried past generations – not an uncontrolled population boom from promiscuity, but a baby bust due to delayed or foregone childbearing.

The latter half of the 20th century thus saw women balancing new opportunities with new challenges. Many attained higher education and entered formerly male-dominated careers (law, medicine, academia, politics). By the 1980s and 1990s, women in Western nations were a significant part of the workforce and increasingly present in leadership roles. Yet, work-family balance issues emerged as a societal puzzle: Who raises the children when both parents work? Should childcare and housework be re-divided? Debates about gender roles persisted, even as overt sexist barriers were slowly dismantled. The image of what a woman could be was no longer monolithic – she might be a homemaker, a CEO, or any combination thereof. This was a profound cultural evolution in the span of a few decades.

As we entered the 21st century, a new factor began to shape behavior and identity for both women and men – the rise of the digital age, with the internet and social media creating an entirely new social environment. For women, this new arena has brought further empowerment in some ways, and new predicaments in others.

The Digital Age: Social Media, Self-Image, and New Incentives

If Schopenhauer thought women were fixated on appearance and socializing, one wonders what he would say about Instagram, Facebook, and TikTok – platforms where millions of people (women especially) curate images of their lives for instant feedback from a global audience. The advent of the internet and social media in the 2000s has changed the landscape of social interaction and self-presentation, and women have been at the forefront of these changes.

Firstly, women use social media in greater numbers and intensity than men. Surveys across different countries show that females are often more active on major social networking platforms. For example, one study of young adults found that women spent significantly more time on social media than men, and were much more likely to be heavy users (5+ hours per day). Platforms like Instagram – a visually driven network revolving around photos, personal updates, and influencers – have a predominantly female user base (in one sample, 65% of young women used Instagram versus 46% of young men). Similarly, Pinterest is dominated by female users, and even TikTok (the short-video app) skews toward more female usage in many regions ( Personal Exposure to Social Media and Variations by Gender among Cuban Youth - PMC ). This isn’t to imply men aren’t online (they definitely are, often gravitating to YouTube, Reddit, or gaming platforms), but social media as a social tool is strongly embraced by women.

One could argue this reflects women’s evolutionary proclivity for social networking and communication – now amplified by technology. Where women once exchanged news over the communal well or at the market, today they might do so via Facebook posts or WhatsApp groups. Social media also offers women a way to bypass traditional gatekeepers and make their voices heard directly. Young women have become influential bloggers, YouTubers, and TikTok creators, building personal brands around fashion, fitness, politics, or everyday life. In doing so, they wield a new form of soft power: the power to influence tastes, norms, and opinions at scale without needing institutional authority.

Platforms like Instagram place a high premium on appearance and aesthetics, which can both empower and pressure women. On one hand, an attractive or creative woman can gather a massive following, monetize her content, and achieve a level of fame and financial independence (e.g. as an influencer or entrepreneur) that might have been impossible before. On the other hand, the attention economy of social media can heighten insecurities and a sense of competition, particularly around looks and lifestyle. Studies have found that exposure to the carefully edited, idealized images on Instagram can lead to increased body dissatisfaction and self-objectification in young women (The effect of sexualized imagery posted by Instagram Influencers on ...). The temptation to present a “perfect life” online may reinforce societal pressures on women to look beautiful, happy, and successful at all times – essentially a new form of the old expectation to be the perfect wife or mother, now extended to being the perfect digital persona.

Social media also altered relationship dynamics. The dating landscape changed radically with online dating apps (Tinder, Bumble, etc.), giving women more direct choice in selecting partners – and also exposing them to an effectively limitless pool of potential mates. This can amplify phenomena like hypergamy (seeking a partner of higher status), because on global apps a small percentage of very attractive or high-status men get disproportionate attention from women, potentially skewing the dating market. Conversely, women who once had few options in a small town can now connect with suitors worldwide, which can be empowering. The overall effect is complex: some research suggests online dating has led to more relationships that cross racial or social lines (by expanding one’s network), but also more casual relationships as the next option is just a swipe away. In any case, the internet has given women (and men) more autonomy in mating choices outside of family or community influence, continuing the trend of decoupling marriage and reproduction from strict social regulation.

Another aspect is how technology enables women’s economic empowerment. Through remote work, e-commerce, and digital platforms, many women can start businesses (selling crafts on Etsy, offering consulting services online) or work flexibly while balancing family, more easily than in the past. The internet has also provided spaces for women-centric communities and activism (#MeToo being a powerful recent example of online feminist mobilization that had real-world impact in exposing sexual harassment).

Yet with these opportunities come new challenges. The dark side of online life – harassment, cyberbullying, unrealistic comparisons – often hits women hard. Female public figures online commonly face vicious sexist attacks or threats, a continuation of historical attempts to silence women now in digital form. And at a psychological level, the “dopamine hits” of social media (likes, comments) create incentives for immediate validation that can be addictive. One might even draw a parallel to Schopenhauer’s note that women have an “inclination for extravagance” and living in the moment – in the social media age, everyone is somewhat pushed to live in the moment of the next notification, but women, being more active on these networks, are especially engulfed in this instant-feedback culture.

Despite these pitfalls, it’s clear that the digital arena has given women a new realm to exercise their traditional strengths – communication, community-building, aesthetic expression – on a global scale. A young woman on TikTok with creative content can influence millions, effectively wielding indirect cultural power that kings and priests of old could only dream of. In that sense, modern technology has further leveled the playing field, allowing women to compete not by the old rules of physical might or closed institutions, but in the open forum of ideas, trends, and online entrepreneurship.

Female Values in Modern Politics and Culture

With women’s full participation in modern society – as voters, workers, and leaders – one may ask: are there discernible “female” values or tendencies that are reshaping our cultural and political order? It’s important to avoid stereotypes; women are a half of humanity and immensely diverse. However, research and historical trends do suggest some aggregate differences in priorities and style between men and women, and these are increasingly reflected in society’s direction.

One well-documented pattern is that women, on average, place more emphasis on peace, stability, and social cohesion in the political realm. Polling data from many countries show a gender gap in attitudes toward war and the use of force – women are consistently less supportive of military solutions compared to men. Scholars have even formulated a theory of a “suffragist peace,” observing that nations where women were empowered earlier tend to have more peaceful policies and fewer armed conflicts ( Diplomatic Double Standards: The Sexism a President Kamala Harris Would Face - Australian Institute of International Affairs). Former U.S. President Barack Obama once remarked that if women ran every country, “there would be less war.” This aligns with evolutionary logic (women as life-givers may be more averse to destructive conflict) and with historical evidence. Steven Pinker, surveying long-term trends, concluded “over the long sweep of history, women have been and will be a pacifying force”, correlating the “feminization” of society with declining violence. We see hints of this in contemporary politics: for example, countries with higher women’s representation often invest more in diplomacy and social programs versus militarization.

Women also often prioritize social welfare, health, and community in policy. A global survey of parliamentarians by the Inter-Parliamentary Union found that women legislators were more likely than men to emphasize issues like education, healthcare, poverty alleviation, and social cohesion in their work ([PDF] Equality in Politics: A Survey for Women and Men in Parliaments). This doesn’t mean men don’t care about these issues, but women (perhaps drawing on traditional caregiver roles or community visibility) bring them to the fore. The expansion of the welfare state in the 20th century, which created safety nets for the young, sick, and elderly, coincided significantly with women’s rising political voice (Women's Suffrage and the Growth of the Welfare State - jstor). For instance, once women got the vote, spending on public health and children’s wellbeing tended to rise. These could be seen as “female” values of stability and care being translated into governance – a shift from an order previously focused more on competition, conquest, and economic growth at all costs.

Another area is the workplace and leadership style. As more women have moved into management and leadership roles, some organizational scholars note a trend towards more collaborative, empathetic, and people-centric leadership (again, these are generalizations with plenty of individual exceptions). The command-and-control model of leadership often associated with “masculine” norms is giving way in many places to an emphasis on emotional intelligence, team cohesion, and work-life balance – changes arguably accelerated by female influence. During crises like the COVID-19 pandemic, some commentators pointed out that countries led by women (e.g. New Zealand under Jacinda Ardern, Germany under Angela Merkel) performed well by emphasizing compassionate communication and precautionary action (like early lockdowns to protect life), reflecting what they termed a “female” approach to crisis management. While it’s hard to draw firm conclusions, it does seem that having women at the decision-making table broadens the perspectives and can lead to policies that value immediate human needs and social unity, perhaps more so than abstract ideology or bravado.

Culturally, the increased prominence of women has shifted norms too. There is arguably more sensitivity to issues of equity, inclusion, and interpersonal ethics – what one might call an ethic of care – in public discourse now than in past eras. Behaviors like bullying or sexual harassment that were once shrugged off are now widely condemned, in large part due to women calling attention to them. Popular culture has also seen a proliferation of content centered on women’s experiences, from literature and film to the blogosphere, contributing to a more holistic social narrative that values family, relationships, and emotional well-being alongside traditional “male” heroics.

Of course, these shifts come with unintended consequences and tensions. Some critics (often men, but also some women) worry that a “feminized” culture might become too risk-averse or present-focused, emphasizing security over innovation or immediate comfort over long-term grit. For example, the drive for safety and inclusion, while laudable, sometimes sparks debates about free speech vs. offensive content, with detractors claiming society is becoming overly protective (pejoratively termed “nanny state” or “cancel culture”). These debates can be seen as part of the adjustment to a new balance of values – finding the right mix of traditionally masculine and feminine approaches in public life. It’s worth remembering that traits like caution, empathy, and consensus-building, stereotyped as feminine, can be invaluable (we have fewer people dying in wars now, partly because of such values ( Diplomatic Double Standards: The Sexism a President Kamala Harris Would Face - Australian Institute of International Affairs). On the flip side, traits like bold vision and abstract thinking, stereotyped as masculine, also remain crucial. Ideally, a modern society leverages the full spectrum of human qualities.

In politics, women leaders sometimes feel pressure to prove they are tough enough – Margaret Thatcher, Golda Meir, and others were called “Iron Ladies” precisely because they had to govern in a male-established paradigm. Yet as female leadership becomes normalized, it may gradually redefine what effective leadership looks like, making it more multidimensional. In the long run, some theorists suggest that as gender roles equalize, we might see diminished polarization of traits – men becoming more nurturing, women more assertive – moving beyond strict gendered behaviors. But as of 2025, we can certainly observe that increased female influence has infused our societies with greater emphasis on stability, immediacy (addressing present social needs), and cohesion.

Conclusion

From ancient matriarchs to medieval mistresses, from Victorian housewives to Instagram influencers, women have navigated a world often structured against their direct empowerment by developing distinct strengths and strategies. Schopenhauer’s portrayal of women as present-focused and wielding indirect influence, though dripping with misogyny, ironically touches on adaptive behaviors women were forced to employ in male-dominated settings. Throughout history, evolutionary pressures and social structures channeled women into roles where attention to immediate relationships, emotional nuance, and covert influence were not just advantageous – they were often the key to survival and impact.

What we’ve seen is a grand arc of transformation: In antiquity and agrarian eras, women’s sphere was largely domestic and their power exercised through family and subtlety. Evolutionary roles persisted under the surface – women as child-bearers and nurturers, men as providers and protectors – but culture gradually modified how those roles played out. The industrial age initially reinforced a stark divide (the separate spheres), yet it also sowed seeds of emancipation as women fought for education and suffrage. The 20th century then brought women rushing into public life – working, voting, controlling their fertility – fundamentally altering age-old dynamics. By decoupling sex from reproduction, technology like the Pill upended millennia of reproductive bargaining, granting women sexual autonomy but also contributing to new social puzzles (such as declining birth rates and redefined family structures.

In modern societies, women have unprecedented freedom to choose their paths, and they are collectively imprinting their values on the world. There is greater peace and interpersonal concern in politics where women’s voices are strong, greater attention to social welfare and the “human” side of policy, and a cultural celebration of narratives centered on empathy and collaboration. At the same time, the rapid changes have not come without friction: gender gaps persist in leadership and pay; work-family balance remains a challenge; some men feel displaced and react with confusion or backlash; and the new world of social media can reinforce as well as relieve the pressures on women.

Ultimately, the story of women’s nature and behavior is not one of a static essence (as Schopenhauer believed) but of remarkable adaptability. Women have shown they can excel in whatever arena they enter – be it sustaining a family through famine, subtly steering a king’s policy, running a corporation, or leading a country. Evolution gave them certain tendencies and toolkits, but those were never absolute limits. If anything, evolutionary history endowed women with a formidable flexibility: the ability to be caregivers and strategists, to endure hardship and embrace change. As technology and social norms continue to evolve, women will no doubt continue to adjust their strategies and values.

Today, a young woman coming of age in a digital, post-feminist-revolution world inherits freedoms her great-grandmother could hardly imagine. She also faces decisions that are uniquely modern – how to carve an identity amid endless options, how to use her voice on global platforms, whether to prioritize career, love, children, or some combination. Beneath the modern trappings, the ancient evolutionary pulls are still there: the draw of companionship, the rhythms of biology, the quest for meaning and legacy. But they play out on a very different stage. We are, in a sense, witnessing an ongoing grand experiment – what happens when the indirect becomes direct, when the historically voiceless half of humanity claims the microphone, when sexual behavior is uncoupled from its ancient consequence, and when female perspective fully joins male perspective in defining civilization’s course.

It is a time of both empowerment and uncertainty. Yet if history is our guide, women will continue to be, as they always have, key agents of social cohesion, survival, and progress – whether through the hearth or the hashtag. The patterns may shift, but the impact endures. As Schopenhauer’s contemporary John Stuart Mill (a far more sympathetic observer of women) wrote in 1869, “The improvement of society, the condition of the people, and the progress of civilization are largely dependent on the elevation and education of women.” That elevation has been long in coming, but it is well underway – and with it comes a rebalancing of human priorities toward the stable, the immediate, and the inclusive, for the benefit of all.

Sources:

- Schopenhauer, A. (1851). On Women. (English translation) (Arthur Schopenhauer. On Women “1865 | by Theodor Svedberg | Medium) (Arthur Schopenhauer. On Women “1865 | by Theodor Svedberg | Medium).

- Zhu, N. & Chang, L. (2019). “Evolved but Not Fixed: A Life History Account of Gender Roles…” Frontiers in Psychology ( Evolved but Not Fixed: A Life History Account of Gender Roles and Gender Inequality - PMC ) ( Evolved but Not Fixed: A Life History Account of Gender Roles and Gender Inequality - PMC ).

- UCL News (2022). “How did patriarchy start – will evolution get rid of it?” (Analysis: How did the patriarchy start – and will evolution get rid of it? | UCL News - UCL – University College London) (Analysis: How did the patriarchy start – and will evolution get rid of it? | UCL News - UCL – University College London).

- Medieval Women and Power (2014). Magistra et Mater blog (Medieval women and power – Magistra et Mater) (Medieval women and power – Magistra et Mater).

- Wikipedia: Separate Spheres (Separate spheres - Wikipedia) (Separate spheres - Wikipedia).

- History.com (2018). “Women of the WWII Workforce” (Women of the WWII Workforce: Photos Show the Real-Life Rosie the ...) (Table of Statistics on Women in the World War II Era Workforce · SHEC).

- NPR (2020). “The Pill 60 Years Ago Helped Change Lives” (How The Approval Of The Birth Control Pill 60 Years Ago Helped Change Lives : NPR) (How The Approval Of The Birth Control Pill 60 Years Ago Helped Change Lives : NPR).

- PBS American Experience. “The Pill and the Sexual Revolution” (The Pill and the Sexual Revolution | American Experience | Official Site | PBS ) (The Pill and the Sexual Revolution | American Experience | Official Site | PBS ).

- Cuban Youth Social Media Study (2023) ( Personal Exposure to Social Media and Variations by Gender among Cuban Youth - PMC ) ( Personal Exposure to Social Media and Variations by Gender among Cuban Youth - PMC ).

- Blair, C.W. & Schwartz, J.A. (2024). “Diplomatic Double Standards…” AIIA ( Diplomatic Double Standards: The Sexism a President Kamala Harris Would Face - Australian Institute of International Affairs) ( Diplomatic Double Standards: The Sexism a President Kamala Harris Would Face - Australian Institute of International Affairs).

- IPU (2008). Equality in Politics: A Survey ([PDF] Equality in Politics: A Survey for Women and Men in Parliaments).

- IHME (2024). “Global fertility rates decline” (The Lancet: Dramatic declines in global fertility rates set to transform global population patterns by 2100 | Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation) (The Lancet: Dramatic declines in global fertility rates set to transform global population patterns by 2100 | Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation).

Apendix. AI reasoning:

Evolution of Female Behavior and Influence from Antiquity to the Digital AgeChatGPT

I’m preparing to structure a comprehensive essay using Schopenhauer’s views and evolutionary biology, spanning women’s history, technology’s impact, and sociocultural shifts.

I’m gathering quotes from Schopenhauer, exploring evolutionary biology, historical roles, and the impacts of contraception and social media on female empowerment and sociocultural trends.

Searched for Schopenhauer on women quotesChatGPT

I’m noting Schopenhauer's perception of women's immediate thinking and indirect influence, reflecting his broader philosophical perspective.

Searched for Schopenhauer quotes on womenChatGPT

Interestingly enough, the Medium.com posting is a reprint of Schopenhauer's "On Women," complete with a specific quote from the text.

Read medium.com

ChatGPT

Schopenhauer's philosophical lens on women is explored, highlighting their short-sighted, present-focused nature, and contrasting these traits with broader evolutionary and historical patterns.

Read more from medium.com

ChatGPT

I'm curious about looking through more content.

Read more from medium.com

ChatGPT

I'm mapping women's social roles from ancient to digital times, considering how technology like contraception and social media shape modern behavior.

I'm noting how contraception and social media have upended traditional gender norms, fostering sexual freedom and indirect female power, while preserving certain evolutionary roles.

Searched for evolutionary psychology sex differences and future planningChatGPT

I'm noting three potentially key papers:

Read pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

ChatGPT

OK, let's decode how gender roles stir differently in high-risk and stable environments. High risk? More traditional. High stability? Ah, now we're seeing the shift.

Read more from pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

ChatGPT

Mapping how contraception and reduced mortality reshape gender roles, enhancing women's economic and social positioning, concurrent to male competition.

Searched for women's indirect power in historyChatGPT

Examining the influence of women in history, particularly through salons and their roles as mothers and wives, reveals substantial indirect political power.

Read magistraetmater.wordpress.com

ChatGPT

I'm starting to see if this line holds the key details we need.

Read more from magistraetmater.wordpress.com

ChatGPT

I’m charting the evolution from antiquity to the digital age, examining women’s roles in ancient civilizations, agrarian societies, and the implications of technological advancements on gender dynamics.

Searched for agriculture and patriarchy impact on women's statusChatGPT

I'm piecing together the correlation between plough agriculture and patriarchal norms. Plough reliance historically reduced female labor participation, skewing societal structures toward male dominance.

Read ucl.ac.uk

ChatGPT

Agriculture led to patriarchy as men controlled resources, used women as reproductive tools, and formalized kinship structures.

Searched for women in the Industrial Revolution and suffrageChatGPT

I'm pulling together how the industrial revolution and middle-class ideals, despite their traditional separation of spheres, sparked significant movements like Seneca Falls and suffrage, leading to notable advances in women's rights and education.

Read en.wikipedia.org

ChatGPT

I’m exploring the ideology of 'separate spheres' during industrialization, with women at home and men in public life, despite early feminist calls for equality.

Searched for impact of contraception pill on women in the 1960sChatGPT

I’m examining how the pill decouples sex and reproduction, considering its effects on women's empowerment, sexual liberation, marriage patterns, moral debates, fertility rates, and the concept of "free love" in the 60s.

Read npr.org

ChatGPT

I'm recognizing how the birth control pill heralded a seismic shift, bestowing women with autonomy over their fertility. This newfound control unlocked avenues for education and careers, reshaping gender dynamics and societal expectations.

Read pbs.org

ChatGPT

The PBS piece explores how the Pill divorced sex from procreation, sparking fears of "sexual anarchy" and women's empowerment, thereby fueling the sexual revolution.

I'm examining how platforms like Instagram, FB, and TikTok are shaping women's behavior, incentivizing beauty, and influencing self-objectification, while potentially fostering a more global and competitive attention economy.

Searched for women Instagram behavior and gender differencesChatGPT

Women are more engaged in social media, especially image-centric platforms like Instagram and Pinterest, and influence sectors like fashion and lifestyle through self-branding.

Read pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

ChatGPT

Women are skewing towards visually-oriented platforms like Instagram and Pinterest, while men are more engaged with text-heavy sites like YouTube. This aligns with contemporary stereotypes.

Searched for Instagram, women, and self-esteem researchChatGPT

Maximizing social media benefits while mitigating mental health risks. Flexing traditional strengths globally.

Searched for global fertility decline and women's educationChatGPT

Acknowledging how separating sex from reproduction has sparked fertility declines and societal changes, like aging populations and altered family dynamics.

Searched for social media dating and hypergamy in womenChatGPT

I'm thinking about women's political values, favoring liberalism, social welfare, and peace, which can influence political outcomes and spending.

Searched for female voters, gender gap, and social welfareChatGPT

I’m examining sources to understand the link between women voting and peaceful policies. Women voters tend to favor peace and social welfare more than men, which consistently skews Democrat in U.S. elections since 1980.

Read internationalaffairs.org.au

ChatGPT

Public polling shows that women generally prefer peace, contributing to a 'suffragist peace' where nations with female voters are less prone to conflict. Women leaders tend to prioritize health, education, and social welfare in their policies.

Searched for women legislators' policy priorities in health and educationChatGPT

I'm thinking about incorporating Schopenhauer's lens, evolutionary differences, historical timelines, social media influences, and political trends to enrich the analysis. Images like the 1857 painting "The Sinews of Old England" or "Rosie the Riveter" could effectively illustrate key themes.

Read upload.wikimedia.org

ChatGPT

I’m trying to determine if removing "/thumb/.../220px-" from the image path might reveal a higher-resolution version on Wikipedia. This could enhance the thumbnail's clarity.

Read more from upload.wikimedia.org

ChatGPT

I'm gathering various image ideas to represent different eras, like an Egyptian queen, medieval tapestry, or Rosie the Riveter, ensuring they align with the "Industrial Era and Separate Spheres" section.

Searched for "Rosie the Riveter" image on WikimediaChatGPT

I'm considering the "We Can Do It!" poster for copyright status. The Miller poster might be PD, but the Rockwell painting surely isn't. The wartime photo, likely from NARA, is a strong PD candidate.

Read en.wikipedia.org

ChatGPT

I’m pulling together the original link, noting the file's resolution as 4036x3224.

Read upload.wikimedia.org

ChatGPT

I'm thinking through the pivotal role women played in the workforce during WWII, especially in industrial jobs, breaking traditional gender roles and showcasing women's skills in the workforce.

Read en.wikipedia.org

Searched for women in the workforce during World War II statisticsChatGPT

I'm examining the progression of women's roles, from early societies to the impact of Schopenhauer's views and evolutionary theories on their influence.

Examining how social media reshapes behavior, privacy, and sexual ethics, I’m analyzing the unexpected shifts in social norms and economic opportunities for women in the digital era.

Searched for women suffrage and welfare spending evidenceChatGPT

I’m outlining sections, considering Schopenhauer's views, evolutionary differences, historical context, and key modern influences like welfare and social media. Delving into gender dynamics and societal shifts, exploring complex themes in women's roles and perspectives.

I'm mapping out women's roles in antiquity and the agrarian era. Discussing patriarchy, patriarchal norms, and societal influences during these transformative periods.

I'm organizing a detailed outline on the impact of women's roles, spanning from antiquity to modern times, incorporating historical shifts, societal norms, and technological advancements.

Searched for feminization of society and empathyChatGPT

I'm gathering info on how greater female empowerment might hasten fertility decline. This shows a valuable link between women's social status and reproductive patterns. Especially noteworthy is the potential impact of decoupling sex from reproduction on global fertility rates.

Read healthdata.org

ChatGPT

I'm adjusting the emphasis on the main idea and stylistic considerations, ensuring a balanced presentation of Schopenhauer's views.

I'm noting that Bing is the preferred search engine, despite the potential for better results from Google.